Books |

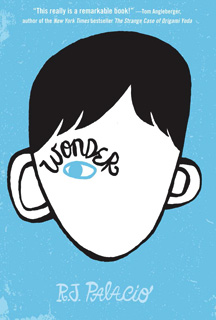

Wonder

R.J. Palacio

By

Published: Nov 12, 2017

Category:

Fiction

The action movies based on comics are pretty much behind us. This is is the season when Hollywood starts releasing its better movies. Like “Wonder,” which stars Julia Roberts, Owen Wilson and Mandy Patinkin.

Some of you may recall that “Wonder” is a Young Adult novel that became an instant class when it was published in 2013.

What I love about good novels — maybe what I love best about them — is how much they make me feel. When you enter the world of a really good book, you surrender to it. Its concerns are yours. Here, through characters that remind you of parts of yourself, you can do something. What looks to a non-reader as an escape from the world is anything but — it’s a confrontation with all the stuff that makes you crazy. Young Adult novels do this with stunning regularity.

The Fault in Our Stars — a Young Adult novel about two teenagers with cancer — was the last YA book that took me over. When I finished reading, I said, “I hated that I’d read it because there was nothing I wanted to do more than read it again for the first time.”

That’s how I felt when I read R.J. Palacio’s “Wonder.” Like “Fault,” this is a YA novel that’s easy for kids to read and challenging for adults to deal with. (Topic for another day: why are the best YA novels so much more engaging — more passionate, most thoughtful, most dramatic — than most adult fiction?)

Like “Fault,” the main character in “Wonder” is an outsider. Auggie Pullman, now 11 and a fifth grader, was born with Treacher-Collins Syndrome, a rare stem cell condition that results in facial deformities — small jaws and cheekbones, distorted ears and poor hearing. Inside, he’s a kid. Outside, he’s a freak.

Does that put you off? Of course. Which is the first reason why you should read this book as soon as you can — always run to the greatest opportunity for personal growth. [To buy "Wonder" from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audiobook on CD, click here.]

You ask: How does a novelist come up with a character like that?

From life.

Palacio was traveling with her two young sons when she saw a girl with misshaped features. She panicked. Rushed her kids away. The girl and her mother, she realized, had to know why. Next realization: This was a moment the mother and daughter experienced many times.

“On the journey home to Brooklyn,” Palacio has recalled, “I could not stop thinking about how the scene had played out. What could I have done differently? Is there something you can do to prepare your kids for moments like that? Was I not teaching my kids something they should have known?”

“Wonder,” a Natalie Merchant/10,000 Maniacs song, came on the radio as she was driving. The lyrics were a dart:

Doctors have come from distant cities/ Just to see me/ Stand over my bed/ Disbelieving what they’re seeing/ They say I must be one of the wonders/ God’s own creation/ And as far as they can see/ they can offer/ No explanation

Things “collided” for Palacio: “The first line came to me, and the whole premise of the novel. The book wrote itself.”

Really, the book spoke itself. The games, the clothes, the concerns — Palacio listened hard to her kids and took notes. (There’s an excerpt below.)

What’s more astonishing is how Palacio is able to frame the great moral drama of middle school. The fifth grade is when life starts to get complicated. Boys notice girls, girls notice boys, cliques form. It’s not an easy time; in some ways, it’s the end of childhood. You may imagine how much harder the school environment is for a boy who has had 27 surgeries, has always been home-schooled and knows his situation exactly: “I won’t describe what I look like. Whatever you’re thinking, it’s probably worse.”

Sending Auggie to middle school, his father says, “is like sending a lamb to the slaughter.” His father has it wrong. Auggie isn’t a lamb. He’s a great kid, and you root for him from page one. He’s smart and funny, and I know you don’t see how this can be possible, but there are laughs along the way. He has terrific parents. His sister isn’t a jerk. He even has a dog that tugs at your heart, and believe me, I am immune to fiction that throws a cute woofer at me.

Tears? I cried a river. And loved every minute I cried. Interestingly, several reviewers have reported that they cried early and often, but their kids — who also loved the book — didn’t cry at all. I think I understand why. Kids don’t know what we do. They see no weakness in kindness. It’s natural to them. It’s only a career effort for adults.

To read “Wisdom” is to remember what cruelty feels like. And what struggle feels like. And what victory over long odds feels like. A fable? Sure. But, most of all, a wake-up call. And a thrilling reading experience.

For kids 11 to 16, this is The Gift. For you, even more so.

EXCERPT

I know I’m not an ordinary ten-year-old kid. I mean, sure, I do ordinary things. I eat ice cream. I ride my bike. I play ball. I have an XBox. Stuff like that makes me ordinary. I guess. And I feel ordinary. Inside. But I know ordinary kids don’t make other ordinary kids run away screaming in playgrounds. I know ordinary kids don’t get stared at wherever they go.

If I found a magic lamp and I could have one wish, I would wish that I had a normal face that no one ever noticed at all. I would wish that I could walk down the street without people seeing me and then doing that look-away thing. Here’s what I think: the only reason I’m not ordinary is that no one else sees me that way.

But I’m kind of used to how I look by now. I know how to pretend I don’t see the faces people make. We’ve all gotten pretty good at that sort of thing: me, Mom and Dad, Via. Actually, I take that back: Via’s not so good at it. She can get really annoyed when people do something rude. Like, for instance, one time in the playground some older kids made some noises. I don’t even know what the noises were exactly because I didn’t hear them myself, but Via heard and she just started yelling at the kids. That’s the way she is. I’m not that way.

Via doesn’t see me as ordinary. She says she does, but if I were ordinary, she wouldn’t feel like she needs to protect me as much. And Mom and Dad don’t see me as ordinary, either. They see me as extraordinary. I think the only person in the world who realizes how ordinary I am is me.

My name is August, by the way. I won’t describe what I look like. Whatever you’re thinking, it’s probably worse.

Why I Didn’t Go to School

Next week I start fifth grade. Since I’ve never been to a real school before, I am pretty much totally and completely petrified. People think I haven’t gone to school because of the way I look, but it’s not that. It’s because of all the surgeries I’ve had. Twenty-seven since I was born. The bigger ones happened before I was even four years old, so I don’t remember those. But I’ve had two or three surgeries every year since then (some big, some small), and because I’m little for my age, and I have some other medical mysteries that doctors never really figured out, I used to get sick a lot. That’s why my parents decided it was better if I didn’t go to school. I’m much stronger now, though. The last surgery I had was eight months ago, and I probably won’t have to have any more for another couple of years.

Mom homeschools me. She used to be a children’s-book illustrator. She draws really great fairies and mermaids. Her boy stuff isn’t so hot, though. She once tried to draw me a Darth Vader, but it ended up looking like some weird mushroom-shaped robot. I haven’t seen her draw anything in a long time. I think she’s too busy taking care of me and Via.

I can’t say I always wanted to go to school because that wouldn’t be exactly true. What I wanted was to go to school, but only if I could be like every other kid going to school. Have lots of friends and hang out after school and stuff like that.

I have a few really good friends now. Christopher is my best friend, followed by Zachary and Alex. We’ve known each other since we were babies. And since they’ve always known me the way I am, they’re used to me. When we were little, we used to have playdates all the time, but then Christopher moved to Bridgeport in Connecticut. That’s more than an hour away from where I live in North River Heights, which is at the top tip of Manhattan. And Zachary and Alex started going to school. It’s funny: even though Christopher’s the one who moved far away, I still see him more than I see Zachary and Alex. They have all these new friends now. If we bump into each other on the street, they’re still nice to me, though. They always say hello.

I have other friends, too, but not as good as Christopher and Zack and Alex were. For instance, Zack and Alex always invited me to their birthday parties when we were little, but Joel and Eamonn and Gabe never did. Emma invited me once, but I haven’t seen her in a long time. And, of course, I always go to Christopher’s birthday. Maybe I’m making too big a deal about birthday parties.