Books |

The Best Memoirs (Part 2)

By

Published: Feb 25, 2018

Category:

Memoir

I recently published a grab bag of The Best Memoirs (Part 1). Here is Part 2. It’s even longer than Part 1.

Fun Home

The story, in outline, is about a father and a daughter. The girl is Alison Bechdel, a lesbian who grows up to be a cartoonist. Her father is Bruce Bechdel, “a manic-depressive, closeted fag.” A few weeks after she tells her parents she’s gay, her father is killed — Bechdel is convinced it was suicide — by a Sunbeam Bread Truck. “Fun Home” is more than a guided tour of an unusual family, it is a disturbing work of art. Yes, art. This isn’t a comic book with superheroes and superfreaks, it’s a powerful scrapbook of drawings that look like photos with brilliant captions and eloquent dialogue bubbles. As an examination of the ways our personal lives are effected by cultural politics, and vice versa, this as good a memoir as any you can name.

Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs

Guest Butler Jane Chafin secretly hoped to find a payload of southern gothic: deceit and scandal, alcoholism, domestic abuse, car crashes, bogeymen, clandestine affairs, dearly loved and disputed family land, abandonments, blow jobs, suicides, hidden addictions, the tragically early death of a beautiful bride, racial complications, vast sums of money made and lost, the return of the prodigal son, and maybe even bloody murder. . . And she did: all of it and more. This is Mann’s personal history from childhood through her life as a wife and mother of three, her development as an artist and emergence as a nationally recognized photographer; as well as histories of the extended family around her.

Joan Didion: The Year of Magical Thinking

First her only daughter took ill. Seriously ill, in-a-coma and near-death ill. And Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne came home from seeing her in the hospital and John sat down to read and have a Scotch. And then “he stopped talking” and “slumped motionless.” Joan had a card in the kitchen with the phone number of a hospital on it — “in case someone in the building needed an ambulance.” She called. People came. They worked on John and then they took him to the hospital. A man was waiting. He was not wearing scrubs. “I’m your social worker,” he told Joan, and, as she writes, “I guess that is when I must have known.” Joan Didion is not a rapid writer, but she wrote “The Year of Magical Thinking” quickly, the better to keep her prose fresh and raw. The book is very far from a howl of pain — though she explores the outer limits of grief, Didion is the kind of writer for whom even feeling passes through the brain. Which is to say that, in addition to her grief, we learn all about her thoughts about grief and her research about grief.

LeBron’s Dream Team: How Five Friends Made History

LeBron epitomizes a certain definition of manhood. As he billboards his Twitter page: “Nothing is given. Everything is earned. You work for what you have.” This book tells how he came to feel that way — and live his beliefs.

“We all we got.” That epigram — from the front of this book — tells you all you need to know about LeBron James’ memoir. This is not a book about basketball. It’s a book about race, about being born black and poor and fighting your way around drugs and gangs and despair to become a decent human being. It’s about character.

Let’s Take the Long Way Home: A Memoir of Friendship

Caroline Knapp was the author of “Drinking: A Love Story.” I wrote about it because some of you surely have issues with alcohol, and I thought it might be of use. And because it’s acutely observed and beautifully written. And because there’s a painful irony here: Caroline got sober, only to die in June of 2002, when she was forty-two, seven weeks after she was diagnosed with stage-four lung cancer. Caroline Knapp had a best friend. Gail Caldwell. Also a writer. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 2001. She too had alcohol issues. Two women writers. Both dog lovers. Both recovering alcoholics. Both living alone, and liking it. Both athletes. Near-neighbors in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Friends. Best friends. One died. The other wrote a book.

Keith Richards: Life

Wild man. Broken tooth, skull ring, earring, kohl eyes — he’s Cpt. Jack Sparrow’s father, lurching though life as if it’s a pirate movie, ready to unsheath his knife for any reason, or none. Got some blow, some smack, a case of Jack Daniels? Having a party? Dial Keith. When you get a $7 million advance for your memoirs, there’s no such thing as a “bad” image. But the thing about Keith Richards is, he wants to tell the truth. Like: he didn’t have his blood transfused. Like: he didn’t take heroin for pleasure or to nod out, but so he could tamp his energy down enough to work. Like: he and Jagger may not be friends but they’re definitely brothers — and if you talk shit about Mick to him, he’ll slit your throat. Why does Keith want to undercut his legend? Because he has much better stories to tell.

Kelly Corrigan: Lift

Corrigan’s love letter to her two young daughters becomes a meditation on Rilke’s line, “The knowledge of impermanence that haunts our days is their very fragrance.” That’s an interesting idea. Especially to parents — we’ve all had it. The ticking clock. How the days are long, but the years are short. How our kids can’t know what they mean to us until they have kids who mean everything to them.

Luck and Circumstance: A Coming of Age in Hollywood, New York, and Points Beyond

Picture a Brit, cigar in his fingers, a glass half full of some golden liquid, the meal finished, the night getting on. He is slim and elegant now, but he is telling you about his childhood, when his nickname was Pudge Hoag. Then, when he is fourteen, his mother takes him to a play rehearsal. He meets an actor, Roddy McDowell. And the director, Sidney Lumet. “A few days later, I, Michael, was back at school and was again Pudge Hoag, but it didn’t matter because I knew where I was going.” Later, he makes rock videos: “With Mick Jagger, I’d suggest, he’d question, I’d clarify, and he’d agree, usually. But with The Beatles, that evening, I found an idea was something to be mauled, like a piece of meat thrown into an animal cage. They’d paw it, chuck parts of it from one to the other, chew on it a bit, spit it out, and then toss the remnant to me, on the other side of the bars.”

Monsieur Proust

In 1913, Marcel Proust’s driver, Odilon Albaret, married a young woman from a small mountain village. Celeste knew no one in Paris, and her loneliness mounted. Proust suggested that she deliver copies of his new book to friends. And so it began. Messenger, housekeeper, confidante, friend, nurse — until his death in 1922, Celeste Albaret spent more time with Proust than anyone else. Indeed, she spent so much more time at Proust’s home than she did in her own. As her memoir attests, she begrudged not a minute of those hours in his service.

Kate Betts: My Paris Dream: An Education in Style, Slang, and Seduction in the Great City on the Seine

Kate Betts, 22 years old, arrives in Paris in 1986. She’s fourth generation Princeton. She’d written her college thesis on the Paris riots of l968 “and the impact of student-worker action on French political consciousness.” And she’s haunted by her parents’ divorce when she was six. Her first smart move was getting herself to Paris, where she scrambled for entry-level jobs, missed her college boyfriend, met a sweet young Frenchman and was adopted by his charming family. And then she was hired as a features writer for M magazine and W, the biweekly society paper, both owned by John Fairchild, the publisher of Women’s Wear Daily.

Perfection: A Memoir of Betrayal and Renewal

January 8, 2003. A pleasant house with a river view in a charming town not far from New York City. Julie Metz, a freelance graphic designer, is working on a book cover in her home office. Her husband Henry, a writer, is resting upstairs. Their six-and-a-half-year-old daughter Liza is in school. And then death enters — Henry’s felled by a pulmonary embolism. He was just 44, the same age as his widow. They had been married for 13 years. Happily married? Well, they entertained a lot — Henry loved to cook, adored a crowd, needed to be the center of attention. But they often fought. And Julie’s taking both Wellbutrin and Celexa. Grief is a pure emotion — in novels. Non-fiction is messier, and in “Perfection: A Memoir of Betrayal and Renewal,” much messier. As Julie’s brother tidies up Henry’s affairs, he discovers Henry had accumulated $40,000 in credit card debt in less than a year. Julie stops her medication. She feels fine. “The source of my calm,” she concludes, “was Henry’s absence.” A month after Henry’s death, this is not an entirely reassuring discovery.

One of These Things First

Steven is 15. On this day in 1962, he’s in the back of his grandparents’ ladies’ clothing store. At a window, he rolls up his sleeves. “And then with all my might I punched through the two lower window panes of glass, one fist through each, one fists, two fists…. and I sawed my wrists and forearms twice back and forth across the shards.”

Patti Smith: Just Kids

At 14, Patti Smith was a “skinny loser,” a frequent occupant of the dunce chair. She was also, God bless her, a reader, “smitten by the book.” Her family was working class — her mother was a waitress, her father a factory worker — so they moved often, ending up in Camden, New Jersey. For her 16th birthday, her mother gave her “The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera.” That summer, as she worked in a factory, inspecting handlebars for tricycles, she dreamed that she was Frida Kahlo, “both muse and maker.” Robert Mapplethorpe grew up on Long Island. He was mischievous and handsome, “tinged with a fascination for beauty.” His family was neat, orderly, Catholic. They weren’t talkers, they weren’t readers. They were “safe.” They met. This is their story.

Rupert Everett: Red Carpets and Other Banana Skins

When he saw his first movie — “Mary Poppins” — “a giant and deranged ego was born.” He dropped out of school at 16 to act. A few years later, he was widely noticed for his film debut, in “Another Country.” In America, his breakthrough came when he more or less stole “My Best Friend’s Wedding” from Julia Roberts. His life, like this book, runs on two tracks. On one, he’s the ambitious actor who never pretends not to be gay so he can become a megastar. On the other, he’s the beautiful diva who’s anywhere and everywhere: “At 17 I had sat with David Bowie downstairs at the Embassy Club and been lectured on the mystical potential hidden in the number seven. At 18 I had dined at La Coupole in Paris with Andy Warhol and Bianca Jagger. I had sniffed poppers with Hardy Amies on the dance floor of Munkberrys. I had done blow with Steve Rubell and Halston at Studio 54.”

Stephen King: On Writing

From paragraph two: “I lived an odd, herky-jerky childhood, raised by a single parent who moved around a lot in my earliest years and who — I am not completely sure of this — may have farmed my brother and me out to one of her sisters for awhile because she was economically or emotionally unable to cope with us. Perhaps she was only chasing our father, who piled up all sorts of bills and then did a runout when I was two and my brother David was four.”

Lesson one: Tell the truth. And skip the charm if none belongs. At six, Stephen wrote a story. Or, rather, copied it. His mother praised it. Stephen was forced to admit it wasn’t original. “Write one of your own, Stevie,” his mother said. “I bet you could do better.” He did. His mother praised it. “Nothing anyone has said to me since has made me feel any happier.” The young writer was launched.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Between the World and Me

This book is a a 155-page letter to his teenaged son. “Here is what I would like for you to know,” he writes. “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body — it is heritage.” If he’s obsessed with the body — especially the bodies of black men — it’s not only because he’s been reading history ever since he went to Howard University, but because the vulnerability of his own body is the first life lesson he learned as a kid growing up in Baltimore.

The Bee Cottage Story: How I Made a Muddle of Things and Decorated My Way Back to Happiness

Frances Schultz has described her East Hampton hideaway as “a little stucco cottage with pretty blue shutters and a big heart.” Works for a description of her as well. Shutters don’t obscure anything; they simply frame a window. And as for the heart…. Here is Frances, on page 1, buying this run-down cottage as “the perfect place to begin my second marriage.” Which didn’t happen. Nice guy, bad fit. And there she was, in “a spot that illuminates the space between where we are and where we thought we’d be… in a sea of fear, self-loathing and self-doubt.” Well, if she couldn’t fix herself, she’d fix the house. It wasn’t much of a goal — “a point of light in a big dark room, but it was something.” Why a house? “Start where you are, begin with what you know.”

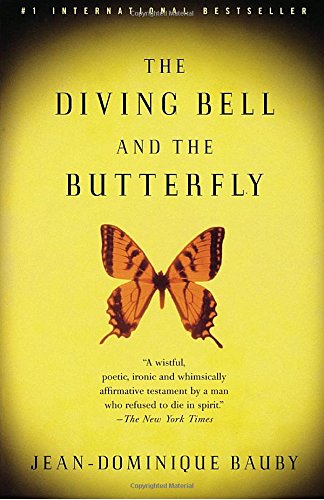

The Diving Bell and the Butterfly

This is what happened to 43-year-old Jean-Dominique Bauby in 1995. One minute he’s a king in Paris: the editor-in-chief of Elle Magazine, father of two, friend to many, a successful man taking a test drive in a new BMW. The next moment he has a stroke that attacks the brain stem. Twenty days later, when he emerges from a coma, he is pretty close to what hospital workers, with their stark lingo, would call a “gork” — he’s completely paralyzed. Except for his left eyelid. He can blink.

The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss

This memoir has everything. The highest echelons of Society in pre-World War I Paris. Nazi thugs and Austrian collaborators. A gay heir who takes refuge in Japan. Style. Seduction. Rothschild-level wealth. Two centuries of anti-Semitism. And 264 pieces of netsuke, the pocket-sized ivory-or-wood sculpture first made in Japan in the 17th century. It is on these netsuke that de Waal hangs his tale — or, rather, searches for it. Decades after he apprenticed as a potter in Japan, he has returned to research his mentor. In the afternoons, he makes pots. And, one afternoon a week, he visits his great-uncle Iggie….

The Last Lecture

One of the staples of “the college experience” at many schools is the “last lecture” — a beloved professor sums up a lifetime of scholarship and teaching as if he/she were heading out the door for the last time. It’s the kind of tweed-jacket-with-elbow-patches talk that may or may not impart useful knowledge and lasting inspiration, but almost surely gives all present some warm and fuzzy feelings. Randy Pausch’s “last lecture” was different in every possible way. The professor of Computer Science, Human Computer Interaction, and Design at Carnegie Mellon University was just 46, and this really was his last lecture — he was dying.

The Thunderbolt Kid

Reader Review: “A few years ago I was on a transit train in late afternoon reading ‘Thunderbolt Kid.’ I laughed so loudly it came out as an unattractive sound followed by more snorting like sounds. The well-dressed businessman beside me patted me on the shoulder and asked politely if I was okay. No, I was almost hysterical while reliving my Midwest Canadian childhood in Winnipeg.”

Bill Bryson was born in 1951 in Des Moines, Iowa. Talk about lucky! “I can’t imagine there has ever been a more gratifying time or place to be alive than America in the 1950s,” he writes. “We became the richest country in the world without needing the rest of the world.” And Billy Bryson — white, Protestant, son of a brilliant sportswriter and the home furnishings editor of the Des Moines Register — was in just the right place to take full advantage.

The Men in My Life: A Memoir of Love and Art in 1950s Manhattan

“In the 1950s, Patricia Bosworth acted with the best, married the worst, and lost those she loved.” That’s the headline of the Los Angeles Times review of Patricia Bosworth’s memoir. It’s an eye-catcher — just as the function of the barker at the carnival is to get you into the tent, the function of a headline is to get you to read the review. And it’s accurate. Bosworth married a monster when she was an 18-year old freshman at Sarah Lawrence. When she was 20, her 18-year-old brother — and her best friend — killed himself. When she was 24, her father, a brilliant and celebrated lawyer who had spiraled into alcohol and drug addiction, fatally overdosed on his fifth suicide attempt. But “The Men in My Life: A Memoir of Love and Art in 1950s Manhattan” isn’t just a memoir of ruin, survival and triumph. As the subtitle suggests, it’s actually two books in one. One is about perseverance and talent and raw courage — about art. The other is about love — really, about sex.

Joan Juliet Buck: The Price of Illusion

Her father more or less discovered Peter O’Toole. Anjelica Huston was her childhood playmate and lifelong friend. Her parents owned a pink marble palace, “a 1900 copy of the Grand Trianon at Versailles, but smaller.” She was writing book reviews for Glamour when she was at Sarah Lawrence. At 22, Andy Warhol anointed her as Interview Magazine’s London correspondent. At 23, she became features editor of British Vogue. The year I met her, she was 32, just starting at American Vogue and writing her first novel.

The Rules of Inheritance

This is a memoir about a bummer. Two bummers, really. When Claire Bidwell Smith, an only child, was 14, both of her parents were diagnosed with cancer. When she was 18, her mother died. When she was 25, her father died. Claire Bidwell Smith is now a grief counselor and hospice worker — she’s not only come to terms with her losses, she’s learned how to use them to help others. “The Rules of Inheritance” is sensationally good, and if you have lost someone you love or are in the process of losing someone, I’d put this book on top of the pile.

The Tender Bar

J.R. Moehringer’s father, a noted disc jockey, was out of his mother’s life before J.R. was old enough to remember that he was ever around. (“My father was a man of many talents, but his one true genius was disappearing.”) His mother, suddenly poor, moves into her family’s house in Manhasset, Long Island. In that house: J.R.’s mother, grandmother, aunt and five female cousins. Also in that house: Uncle Charlie, a bartender at Dickens, a Manhasset establishment beloved by locals who appreciate liquor in quantity— “every third drink free” — and strong opinions, served with a twist. A boy needs a father. If he doesn’t have one, he needs some kind of man in his life. Or men, because it can indeed take a village

Tina Brown: The Vanity Fair Diaries, 1983-1992

ina Brown was a once-in-a-lifetime creative force in a business that generally rewarded dull competence. She set the bar high (“Always do the impossible thing first”), urged writers to have a big life (“Go out, go out, and bring something back, even if it’s only a cold”), and took her greatest pleasure in marking copy with a red pencil (“It’ll cut like butter.”) These days, when New York media folk tell me how hard they work, I just smile. And think, “Not compared to Tina Brown.” Her diaries are a record of her creativity, decisiveness and pluck. For those who didn’t discover her crisp prose in “The Diana Chronicles,” the diaries also reveal that she is a wickedly good writer.

Walking Through Walls

In the 1950s, he had a great career as an interior decorator — “the only heterosexual decorator in Miami” — with clients ranging from the Old Guard in Palm Beach to dictators in the Caribbean. His wife was stylish. Philip, his only son, was happy. The cracks in normalcy start early in Lew Smith’s story, when he moved his family to an area known as “unincorporated Dade County. This jungle on Miami’s fringes featured snakes, undrinkable water, no phones — and very weird neighbors. “Sometimes I saw Mr. Carter leave the house in a shimmering white gown as he headed off to his Klan meeting,” Smith writes, recalling his childhood. “There was a lemon-yellow trailer parked at the rear of the property. Presumably, this was the spaceship that brought these aliens down from Loxahatchee or whatever hick planet they were from.” In 1962, as his son worried about the Cuban missile crisis, his father shared a different concern. “I have sanpaku,” Lew announced. “There’s too much yang in my body.” And it wasn’t just him, he said — his wife and boy were also toxic. A macrobiotic diet followed. And homeopathic medicine. Soon Lew was into yoga, reincarnation, Krishnamurti and Madame Blavatsky, kundalini and Atlantis. Philip, in contrast, was into escape: “I wanted a complete brain job that would remake my life free of the supernatural influence. I was hoping that there was some sort of magic pill that could suddenly turn me into a normal kid, something I simply did not know how to be.”

Wear and Tear: The Threads of My Life

Tracy Tynan is the daughter of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Really. Her father, Ken Tynan, was the bad boy of the English theatrical world. Her mother, Elaine Dundy, was a gifted novelist. But their real talent was for excess. They were loud. Drunk. Unfaithful. Whatever they touched, they broke. Scott and Zelda. They did not break their only child, who should be a basket case and is, instead, a triumph of our species. I thought Tracy was surprisingly sane when I met her in 1973; as I got to know her story, my admiration increased. It is no surprise to me that all these years later she has written a book that presents itself, modestly, as a memoir organized around the clothes she wore along the path and, when she realized she could make a living using her fascination for clothes, the clothes she chose for the movies she worked on. “Memoir” and “Fashion” are too small a frame