Music |

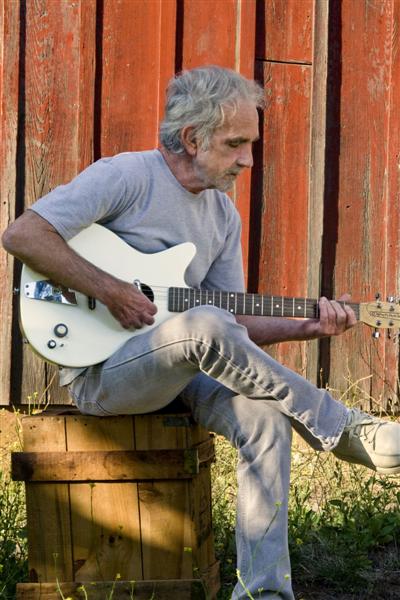

J.J. Cale

By

Published: Jan 23, 2024

Category:

Rock

J.J. Cale died on July 26th, 2013, at 74. If your interest in music is more than casual, you may know that Eric Clapton did not write “Cocaine” and “After Midnight” — J.J. Cale did. If you’re a connoisseur, you know more: Cale was a giant, a protean figure, bound for the pantheon — an immortal.

As a guitarist, Cale stands alongside Hendrix as an innovator. It’s a funny pairing, for Cale was the exact opposite of Hendrix. His playing was minimal, in no way showy. It’s not overstatement to suggest that Clapton owes him at least one of the last decades of his career. Mark Knopfler would admit he learned a thing or three from Cale. And there were others. When was the last time Eric Clapton played rhythm guitar? Well… here.

His guitar style was just the first reason to be awed by Cale. Another was his creative vision. He knew how he wanted his songs to sound, and he knew how to get them to sound that way. On many of his records he played all the instruments (with one exception: he used a drum machine) and sang backup. Then he mixed and produced the record. A one-man band, literally.

And then there is his writing. The titles suggest simplicity: “Call the Doctor,” “Crazy Mama,” “Don’t Go to Strangers.” But the songs are not at all simple — they defy categorization. Country, blues, jazz, shuffle, Okie rock: Cale’s music cuts across genres. The common thread: you have to tap your feet. “He’s good in a studio,” a Tulsa friend said. “But you really want to hear him when he’s playing on the back porch…” [To buy the CD from Amazon, click here. For the MP3 download, click here.] Need more convincing? Here’s “Crazy Mama.”

Cale knew how good he was. But he was a laid-back guy who got a late start. He wasn’t used to personal publicity, and the songwriting residuals were significant — if he didn’t run from the spotlight, he certainly retreated from it. (It wasn’t until late in his career that he allowed his picture to be on the cover of his records.)

Over 35 years, there weren’t many records. (A friend has said, “Cale is very busy being unbusy.”)

At most, 50 live performances a year. (I once saw him perform with his gaze on a music stand. There was no music on it. Can you spell p-e-r-v-e-r-s-e?)

On the subject of a new CD: “I played with some of these guys 40 years ago and I tell you, I don’t think there’s anyone on this record who’s under 60 years old.” (That’s not marketing.)

A story: Cale was pleased when Clapton recorded “After Midnight” in 1970. His pal, producer Audie Ashworth, was more than pleased. “I phoned Cale,” Ashworth recalled, “and I said, ‘It might be time for you to make your move. Get your songs together. Do an album.’ He said, ‘I’ll do a single.’ I said, ‘It’s an album market.’ He said, ‘I don’t have that many songs.’ I said, ‘Write some.’ Three or four months later he called me. He said, ‘I got the songs.’ He drove in. He played me all those songs.”

If Cale’s blend of genres was like nothing else in music, so was his sense of privacy. He got booked on a tour with Stevie Winwood and Traffic. On his days off, he flew back to Tulsa.

You can hear how self-effacing he was in the way he recorded.

As Ashworth has noted, “Cale always wanted the voice mixed down. We’d be sitting at the board and both of us were trying to get our hands on the faders. He was always pulling back the fader on the vocal. He’d mix his voice back in the bed. He said it made you want to lean into the music instead of leaning back from it. It would pull people in. He had definite ideas about mixes.”

Maybe that’s not self-effacing. Because that’s exactly what Chopin did. And you do lean in and lap up every note — of which, because Cale was very very smart, there are very very few.

A flawless career. No false moves. Working hard. Making it look easy. A role model? We could do worse.