Books |

The Orchard

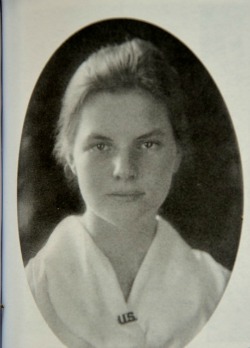

Adele Crockett Robertson

By

Published: Mar 31, 2014

Category:

Memoir

After Adele (Kitty”) Crockett’s father died in 1932, the family gathered in Ipswich, Massachusetts to discuss the fate of their farm. Not an easy conversation — it was a venerable local landmark, the home of Crockett apples, some plucked from trees planted before the Revolutionary War. But this was the bottom of the Depression. Banks were seizing hundreds of thousands of farms. And the Crockett farm was heavily mortgaged, a ripe candidate for seizure. Adele’s mother and two brothers couldn’t be blamed for voting to let the bank have it.

Adele’s father believed the apple and peach orchards would pay for his retirement. And his only daughter “wanted to preserve what we’d had.” Was she a veteran farmer? Anything but. She’d graduated from Radcliffe in 1924 and landed a job in Hartford, Connecticut at the oldest public art museum in the country. Now, at 31, she quit her job, got on a tractor and began to tend acres of peach and apple trees.

From 1932 to 1934, Adele kept a diary. Her daughter found it in 1979, soon after her mother’s death. She added a preface and an epilogue, found a publisher, and, in 1995, “The Orchard” was published.

After I wrote about my desire to help create a residential community around a farm, thoughtful reader Jane Cox suggested I might like this memoir. Never was a suggestion more understated — “The Orchard” is a classic several times over. It’s not only a chronicle of a daughter’s heroic effort to keep her family’s legacy alive, it’s a stunning account of life in the Depression promise. And for a woman who was up at five and working hard until sunset, she’s a remarkably alert writer. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.]

Like this:

The farm, the beloved farm… the trees, each an individual. I came to know them so well. They would do everything — finish my younger brother’s education, pay off the mortgage and the other bills that so embarrassingly we could not settle. Best of all, they would justify my father’s faith in them and confound the doubters. I felt a wonderful surge of strength and pride. I sang and whistled and rejoiced as I rattled along on the tractor. After the long, hot, hard day I fell happily into my bed and woke refreshed in the beauty of the dawn.

That’s the first year, when summer visitors rented the farmhouse, providing needed cash, and she harvested 4,500 boxes of apples. Along the way, people rallied around her. A wonderfully varied crew, from the apple picker and musician Joe LaPlante and the food buyer from Harvard. A lovely contrast from the inevitable villains: the banker eager to foreclose, the poachers who had to be dissuaded with a gun, the freezing winters.

But there was a cost: “The farm could be made to pay, of that I was sure. But to do it I should have to be alone. Too big for one, too small for two.” Well, she’d think of something. And that is what finally makes this book so moving: her relentless optimism, her simple refusal to fail.

Later, in midlife, Adele Crockett Robertson became a much-beloved writer in Ipswich. Her daughter collected her pieces from the local paper in a book that gives a vivid sense of life in the town and her love of sailing and rowing. [To buy “Measuring Time — By An Hourglass” from Amazon, click here.] In 1978, she filed a piece and, a few hours later, died. Local flags flew at half-mast. I call that a good ending.