Books |

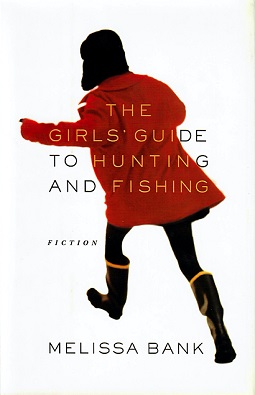

The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing

Melissa Bank

By

Published: Aug 28, 2022

Category:

Fiction

“The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing” was published in 1999. I inhaled it. The characters were people I kind of knew. They spoke the way I wanted my characters to speak. I developed a crushette on Melissa Bank. I could have written a fan letter. I didn’t. This summer, age 61, she died. All these years later, when she can’t read my praise, this is my fan letter.

“Girls’ Guide” was a monster success. While she was still polishing her stories, one was published in Francis Coppola’s magazine and suddenly this unknown writer was getting a big advance. The book became a best seller, was translated into dozens of languages, and sold more than 1.5 million copies. [To read an excerpt, click here. To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Timing is everything. Young urban women navigating careers, sex and romance were a thing in fiction then. You may recall “Bridget Jones’ Diary” and “Ally McBeal” and “Sex and the City.” They were nothing like “Girls’ Guide,” but Bank’s stories were categorized in that unfortunately named genre: “chick lit.” If you avoid them now, it’s largely because you’ve condemned them to that gulag. Mistake. Very big mistake.

Bank is hunting much bigger game in these stories, which track Jane Rosenal from age 12 to her 30s. In chick lit, the women have what I’d call “happy problems.” In Bank’s fiction, white privilege offers no comfort. If anything, it intensifies the angst. Her characters are good talkers, but their cleverness conceals an inability — or unwillingness — to deal with their feelings. Talking isn’t to communicate. It’s insider code, repartee, deflection, cover.

At 12, Jane describes her brother: At one dinner, he ate his Silver Queen corn on the cob “like a normal person, instead of typewriter-style — usually, he’d tap the corn at the end of a row and ding.” Her mother “wore the mask in the family.” Her brother’s girlfriend is a dancer from the Midwest. When she first arrived in New York, the dope dealers in Washington Square said, “Loose joints, loose joints.” And she said, “Thank you.”

In the second story, Jane is in her 20s and has a boyfriend, and they’re in the Virgin Islands. He seems to be paying too much attention to another woman. A friend tells her that the best man she’ll ever find will be attracted to other women. Everything’s complicated; “Here we are on Day Six of our visit, having a Day One conversation.” They squabble. “It scares me how fast I go from disliking to loving him, and I wonder if it’s this way for everyone.”

At 25, she’s an editorial assistant in a publishing house when she meets Archie Knox, 25 years older and the editorial director at another house. Her boyfriend is in Paris, “trying to figure out what he was doing with his life — which is what he was doing with his life.” She and Archie banter. Gossip is freighted. He tells Jane, “While Bogart was dying, Lauren Bacall slept with Frank Sinatra. Don’t ever do that to me, okay, honey?” It’s a fair question: He has trouble with sex. And more with alcohol. She leaves him. He writes a novel about them. I won’t give away the last sentence.

Another story starts with this: “My father knew he had leukemia for four years before telling my brother and me.” She’s reunited with Archie Knox, now in AA. She takes a leave from her job to be with her father. Living at her parents’ home, she thinks: “the quiet in the suburbs has nothing to do with peace.” Then Archie has a medical event and is hospitalized. Who needs her more?

In another story, the perfect guy appears. She senses he’s dangerous… but he’s perfect. Then his anger flares. At everyone and everything. He takes her to Paris. She finds the engagement ring in his bag and… I won’t spoil it.

And, finally, she reads a book like “The Rules,” which told women to dress sexy and be unavailable. She tries the method. Failure is certain. She abandons it. The book ends happily. Happily? Yes. Bank told an interviewer: “Someone asked me how the book might be described. I think it would be ‘Girl meets boy, girl loses self, girl gets self.'” That’s great news. You win the game — succeed in the hunt — by finding yourself.

The Times reviewer missed all this. She — of course, the reviewer was female — was brutal:

I imagine her readers as Starbucks-swilling, “Friends”-watching female denizens of the Upper West Side. The effect is progressively irritating. In place of character development and structure, we are treated to a certain generic weariness throughout, as if to explore Jane’s (or her charming yet ineffectual boyfriends’) actual feelings or motivations would end up revealing something we had all read about before.

Well, that’s proof reviews don’t matter as much as New York smarties think. The book was compelling them, and maybe, more now with time, we see more clearly how the world works. Melissa Bank, for example. She died of lung cancer. She didn’t smoke.