Books |

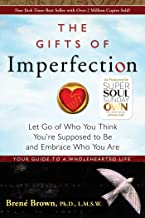

The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are

Brené Brown

By

Published: Mar 16, 2021

Category:

Psychology

I’m closing in on THE END of a novel. It’s set in the present, but it draws on ancient wisdom. As is my custom, I’ve read all the classic texts. It recently occurred to me to see what modern wisdom looks like, on the theory a recent book might deliver fresh insights.

A therapist friend suggested Glennon Doyle. Excellent choice. She had a #1 New York Times bestseller last year with Untamed (two million copies sold), and her previous book, Love Warrior, was also a #1 Times bestseller. Her message is her naked, messy self. Forget who Society wants you to be, she says. Be yourself, your totally honest, wild, authentic self.

Halfway through “Untamed,” the air went out of the book for me, as it often does when someone reveals more than she intends — in this case, flaming monomania. I wasn’t the only one who didn’t join Doyle’s cult. In March of 2020, before the world was divided into the privileged and the struggling and we had to acknowledge that privilege is a bubble, and a particularly insidious one at that, a reviewer nailed the flaw in Doyle’s theology:

Agency is essential in “Untamed” — the ability to trust oneself is, according to Doyle, the key to so-called freedom. But there are things individuals can do and things they can’t, often based on outside constraints. Doyle swings between recognizing this and insisting that women have everything they need inside them. Often overusing the words “power,” “freedom,” “Knowing” and “Self,” “Untamed” reads like a self-help book for wealthy white women.

As luck would have it, soon after I put my copy of “Untamed” in the Goodwill bag, Kara Swisher interviewed Brené Brown for the Times. I have known Ms. Swisher for 20-odd years, and I can tell you she has lived her authentic, honest self every minute of those years. She is a fearless, relentless interviewer, with a lightning brain and a sword for a tongue. Interestingly, the headline of the interview is Can Kara Swisher Be Vulnerable? Incredibly, Brown turns the tables on Swisher, with insistent and masterful questioning that is such delightful reading — go there! go there right now! — I actually looked forward to her book.

“The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are” is short (125 pages) and cheap ($6.99 in paperback at Amazon), a time-expense ratio that is very appealing to this skeptical reader. Good news: “Just thinking about meditating makes me anxious. When I try to meditate, I feel like a total poser.” She knows that the “wisdom” in self-help books is often shallow as glass: “There are too many books that make promises they can’t keep or make change so much easier than it is. The truth is that meaningful change is a process. It can be uncomfortable and is enough risky.”

Her goal is “wholehearted living.” That means “engaging our lives from a place of worthiness… It means looking the world in the eye and saying, ‘I am enough.'”

That is a high bar, for me, anyway. My daughter, at a college 3,000 miles away, recently turned 19. I’d just started Brown’s book, and had read this: “We cannot give our children what we don’t have.” In the middle of my daughter’s birthday night, I woke from a dream with a single, terrible sentence in my head: “I could have done so much better.” And not just for her. For everyone, starting with me.

So, yes, I marked this book up. And I bought Brown’s message, which is the self-help equivalent of blood, sweat and tears: “courage, compassion, and connection.” Why she thinks of herself as a “shame researcher.” How courage means “putting our vulnerability on the line.” How “love is the mirror image of shame.” And “hope is not an emotion, it’s a way of thinking or a cognitive process.” And “is spirituality a necessary component for resilience? The answer is yes.” And and and…you get the idea: Brown’s a lot more than a compelling storyteller. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

EXCERPT: THE START OF THE PREFACE

Once you see a pattern, you can’t un-see it. Trust me, I’ve tried. But when the same truth keeps repeating itself, it’s hard to pretend that it’s just a coincidence. For example, no matter how hard I try to convince myself that I can function on six hours of sleep, anything less than eight hours leaves me impatient, anxious, and foraging for carbohydrates. It’s a pattern.I also have a terrible procrastination pattern: I always put off writing by reorganizing my entire house and spending way too much time and money buying office supplies and organizing systems. Every single time.

One reason it’s impossible to un-see trends is that our minds are engineered to seek out patterns and to assign meaning to them. Humans are a meaning-making species. And, for better or worse, my mind is actually fine-tuned to do this. I spent years training for it, and now it’s how I make my living.

As a researcher, I observe human behavior so I can identify and name the subtle connections, relationships, and patterns that help us make meaning of our thoughts, behaviors, and feelings. I love what I do. Pattern hunting is wonderful work and, in fact, throughout my career, my attempts at un-seeing were strictly reserved for my personal life and those humbling vulnerabilities that I loved to deny. That all changed in November 2006, when the research that fills these pages smacked me upside the head. For the first time in my career, I was desperate to un-see my own research.

Up until that point, I had dedicated my career to studying difficult emotions like shame, fear, and vulnerability. I had written academic pieces on shame, developed a shame-resilience curriculum for mental health and addictions professionals, and written a book about shame resilience called I Thought It Was Just Me.

In the process of collecting thousands of stories from diverse men and women who lived all over the country–ranging in age from eighteen to eighty-seven–I saw new patterns that I wanted to know more about. Yes, we all struggle with shame and the fear of not being enough. And, yes, many of us are afraid to let our true selves be seen and known. But in this huge mound of data there was also story after story of men and women who were living these amazing and inspiring lives.

I heard stories about the power of embracing imperfection and vulnerability. I learned about the inextricable connection between joy and gratitude, and how things that I take for granted, like rest and play, are as vital to our health as nutrition and exercise. These research participants trusted themselves, and they talked about authenticity and love and belonging in a way that was completely new to me.

I wanted to look at these stories as a whole, so I grabbed a file and a Sharpie and wrote the first word that came to my mind on the tab: Wholehearted. I wasn’t sure what it meant yet, but I knew that these stories were about people living and loving with their whole hearts. I had a lot of questions about Wholeheartedness. What did these folks value? How did they create all of this resilience in their lives? What were their main concerns and how did they resolve or address them? Can anyone create a Wholehearted life? What does it take to cultivate what we need? What gets in the way?

As I started analyzing the stories and looking for re-occurring themes, I realized that the patterns generally fell into one of two columns; for simplicity sake, I first labeled these Do and Don’t. The Do column was brimming with words like worthiness, rest, play, trust, faith, intuition, hope, authenticity, love, belonging, joy, gratitude, and creativity. The Don’t column was dripping with words like perfection, numbing, certainty, exhaustion, self-sufficiency, being cool, fitting in, judgment, and scarcity.

I gasped the first time I stepped back from the poster paper and took it all in. It was the worst kind of sticker shock. I remember mumbling, “No. No. No. How can this be?”

Even though I wrote the lists, I was shocked to read them. When I code data, I go into deep researcher mode. My only focus is on accurately capturing what I heard in the stories. I don’t think about how I would say something, only how the research participants said it. I don’t think about what an experience would mean to me, only what it meant to the person who told me about it.

I sat in the red chair at my breakfast room table and stared at these two lists for a very long time. My eyes wandered up and down and across. I remember at one point I was actually sitting there with tears in my eyes and with my hand across my mouth, like someone had just delivered bad news.

And, in fact, it was bad news. I thought I’d find that Wholehearted people were just like me and doing all of the same things I was doing: working hard, following the rules, doing it until I got it right, always trying to know myself better, raising my kids exactly by the books…After studying tough topics like shame for a decade, I truly believed that I deserved confirmation that I was “living right.” But here’s the tough lesson that I learned that day (and every day since):

How much we know and understand ourselves is critically important, but there is something that is even more essential to living a Wholehearted life: loving ourselves.

Knowledge is important, but only if we’re being kind and gentle with ourselves as we work to discover who we are. Wholeheartedness is as much about embracing our tenderness and vulnerability as it is about developing knowledge and claiming power.

And perhaps the most painful lesson of that day hit me so hard that it took my breath away: It was clear from the data that we cannot give our children what we don’t have. Where we are on our journey of living and loving with our whole hearts is a much stronger indicator of parenting success than anything we can learn from how-to books.

This journey is equal parts heart work and head work, and as I sat there on that dreary November day, it was clear to me that I was lacking in my own heart work.

I finally stood up, grabbed my marker off the table, drew a line under the Don’t list, and then wrote the word me under the line. My struggles seemed to be perfectly characterized by the sum total of the list. I folded my arms tightly across my chest, sunk deep down into my chair, and thought, This is just great. I’m living straight down the shit list.

I walked around the house for about twenty minutes trying to un-see and undo everything that had just unfolded, but I couldn’t make the words go away. I couldn’t go back, so I did the next best thing: I folded all of the poster sheets into neat squares and tucked them into a Rubbermaid tub that fit nicely under my bed, next to my Christmas wrap. I wouldn’t open that tub again until March of 2008.