Books |

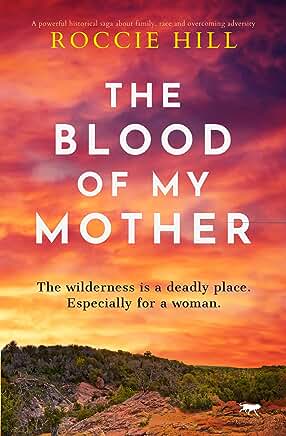

The Blood of My Mother

Roccie Hill

By

Published: Sep 25, 2023

Category:

Fiction

A family of refugees walks a thousand miles to a new home where they’ve been told they can find land to farm. One of them, Eliza, is a young mixed-race girl — and the great-great-grandmother of Roccie Hill, author of “The Blood of My Mother.” This story starts in 1827, when the promised land, now Texas, was part of Mexico. Refugee families “travelled in packs like hounds for survival.” This centuries-old irony is not lost on the novelist or the reader.

Eliza comes from the union of her Anglo drug addict father and a mixed-race delta woman who died in childbirth. Her father was a sharpshooter. People noticed. He fought the Mexicans, made good money — in 1800s Texas, he’d found his calling. But when her father dies, her Uncle James set about building the biggest plantation in Texas. Workers? He secretly bought ten Negroes in New Orleans. Eliza’s sister Lou was white, so she was sent to be fed, clothed and educated. Eliza was not as pretty or as untainted. She got nothing. She was, she tells us, “a girl without value.”

Eliza is sold by her uncle into slavery. There begins this story about what it takes to survive as a refugee, the outcasts Eliza collects along the way, and the strength she, an outcast herself, shows them. “But enduring is not healing or prevailing,” she writes. “It is only persevering; this, a refugee’s rough duty.”

This isn’t a novel told by some white guy who read a history textbook. It’s not about big moments of battle courage. It’s about events you never heard of, like the Runaway Scrape: thousands of settlers walking across Texas in the rain for weeks to escape, hundreds dying along the way. It’s about white children kidnapped by Comanches who never wanted to be “rescued” because their indigenous culture made so much more sense. It’s about the very personal moments during the clash of indigenous, Mexican, and white cultures on the prairie. It’s about women who persevered, because in the end, that’s the only privilege they are ever granted: the right to persevere.

During an early escape, a starving man rushes Eliza on the riverbank, grabbing for her arms and head. She jerks her rifle high and pulls the lever clean and swift. “That was the first time I ever killed a man,” she writes. “You want to know what killing him felt like? Didn’t feel like anything.”

Roccie Hill’s great-great-grandmother could not possibly have imagined her story could be told with sensitivity and eloquence. “The Blood of My Mother” is the third excellent Roccie Hill novel I’ve reviewed —I’ve praised Three Minutes on Love and Window of Exposure. Not just because it’s freshest in memory, “The Blood of My Mother” strikes me as a quantum leap, one of the more beautifully written novels I’ve read in the last few years. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. To buy the Kindle edition, click here. For the audiobook, click here. ]

Some examples:

Eliza makes a pilgrimage to her mother’s grave near Vicksburg: “I tipped like a soggy harlot from side to side as I walked to her. I knelt and put my head on her mound, and spread my arms wide out. What I came for was release from her shawl of mother-tide. What I came for was myself…At last, I sat back on my heels and crossed my arms over my chest. In the thin light of dusk, I read my mother’s name again, the rough letters gouged by my father into her grave marker. There lay his love, deep in the stone, past the gleam of this day, or any day. He had dragged me from her resting pace away to lands so far, but sometimes I saw her spirit sitting at the foot of my bed, still watching me and thinking…. I took a gulp of milk from the can that Teddy Blue handed me, and across the Glass Bayou I saw a swan swimming to the far bank. Beside me, sprouts of barley were growing up out of my mother’s grave. There are no instructions for escaping, nor for letting go. Lift that shawl, I prayed. Let me breathe and love me still.”

Forced to exhume her sister’s body by the local police: “I shouldered what my father would have called manhood, the prying open of the nails, my dead sister with glistening eyes in a dull-brown shroud; I stood it all and took a last long look at her reddened skin and sudden bloated belly, and sucked the smells of her death as though I was inhaling the water of violets. Love does not stop at death; it is protected and petrified, and stored to rise again.”

We want her to survive, and she does. She’ll marry a smart, loyal man. There will be children. She’ll have a small farm. Do you think she’ll keep it without a struggle? Who will help her? People like her — outcasts. Will she have to kill again? Believe it. She’ll raise six children “in kindness, blood kin or not.”

We live now in times of soul-crushing cruelty, seemingly with no respite. A book like this is a glimpse of the kindness we seek; that feeling is hard to forget. Read it now, because it’s likely to be better than the eventual mini-series.