Books |

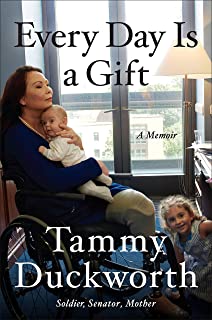

Tammy Duckworth: Every Day Is a Gift

By

Published: Apr 05, 2021

Category:

Memoir

In the rarefied world of celebrity ghostwriters, Lisa Dickey is the gold standard. She has worked on 20 books, and ten have become New York Times bestsellers. She wrote her own book, Bears in the Streets: Three Journeys Across a Changing Russia, an original, insightful account of her travels in Russia over two decades. And then she returned to ghostwriting. Perhaps you’ve heard of the woman she last helped: Jill Biden. And now… Tammy Duckworth.

We all know, in broad outline, the Tammy Duckworth story. American father, Thai mother. She becomes “a little Asian girl who was starving in Hawaii,” keeping her desperately poor family afloat with any odd job that brings in a few coins. Against great odds, she becomes a U.S. Army National Guard helicopter pilot. On November 12, 2004, she’s a 36-year-old Captain piloting a Black Hawk to her base in Iraq when it’s shot down. Her crew hauls her out, convinced she’s dead. When she wakes up, she learns she’s lost both legs and one arm is damaged. She spends 13 months recovering. She writes letters in support of veterans, is noticed by politicians, becomes a candidate. She’s elected to the House of Representatives, then the Senate. At 50, she becomes a mother. Her defining qualities are commitment and fearlessness. When Trump disparages the military, she takes to the Senate floor: “I will not be lectured about what our military needs by a five-deferment draft dodger.” And now we have her memoir. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audiobook, narrated by the author, click here.]

There is so much to admire in these pages, so many compelling scenes. I’ve chosen to excerpt the book’s final pages. That’s against custom. But there are no spoilers at the end of “Every Day Is a Gift.” There is only Tammy Duckworth’s remarkable ability to experience even the worst, move on, and help people who need help and rarely get it. We don’t see that often enough. It’s an honor to share it with you here.

A decade and a half after the shootdown, I had more blessings than I could count. I had a seat in the greatest deliberative body on earth, the U.S. Senate. I had good health, peace of mind, and a couple of kickass titanium legs. And I had my husband, who’d seen me through everything it took to make it this far, and our two beautiful girls.

Now, there was just one more piece of unfinished business to take care of.

In April of 2019 I returned to Iraq, not as a Soldier, but as a Senator. As a member of the Armed Services Committee, I led a Congressional delegation with Senators Johnny Isakson and Angus King to receive operational and intelligence updates on the ground. I was excited to go back, because in addition to the goals of the CODEL, I had a personal goal to fulfill. Almost fifteen years earlier, I had been whisked out of Iraq unconscious, gravely injured, on a Medevac aircraft. This time — for the first time — I wanted to leave Iraq under my own power. I had a score to settle.

The CODEL was scheduled to last just five days, because I didn’t want to be away from Abigail and Maile for longer than that. With one day on each end for travel, that left three days to pack in meetings with Iraqi and Kurdish leadership, American diplomats and Army personnel. We’d be staying in the U.S. embassy compound, which was located in the Green Zone, where I’d had that beautiful stir-fry lunch and milkshake, and bought those little Christmas ornaments of Babylon, all those years ago.

Being in Iraq definitely stirred up old emotions. It’s always hard for me to watch Soldiers going about their business, because I want nothing more than to be one of them again, enjoying the camaraderie and feeling the sense of purpose I’d always felt in uniform. But being a civilian among Soldiers in a combat environment was particularly unsettling. What made it even harder was that we’d be traveling around the Iraqi interior in helicopters, and I’d have to sit in the rear, rather than up in the cockpit where I belonged.

On our first morning after arriving in country, we were scheduled to fly in a Chinook helicopter from the U.S. embassy compound in Baghdad to Taji. A Soldier handed everyone body armor, and while the other Senators struggled to figure out how to get theirs on, I quickly slipped my arms through and fastened it tight. Oh, yes, I thought. There it is. This was pure muscle memory: zip, zip, zip, Velcro straps, helmet on, ready to go. I hooked my thumbs into my body armor, comforted by its familiar heft.

As we walked to the Landing Zone — the same LZ where I had taken off and landed hundreds of times during my deployment — I took a deep breath, and there it was: a smell so familiar, it felt like a part of me. The hot metal of the aircraft, the powdery dust, the whip of the rotor wash, the hydraulic fluid and JP-8 fuel. I heard the growl of the engine, saw the whirl of sand rise under the spinning rotor disc. When the helicopter rose into the sky, I was no longer in 2019 — I was back with my crew in 2004, in the thick of the war. Lifting above the Baghdad skyline, with the Tigris to our east and the desert stretching out beyond the city, I felt the tears welling up.

Being back in a helicopter in Iraq was emotional enough. But later that day, one of the pilots informed me that they had a surprise for me. “Senator,” he said, “We’d like to fly you over the spot.” After researching the grid coordinates from reports filed on the day of the shootdown, they could pinpoint the location where my Black Hawk had gone down — and they wanted to take me to see it.

I had no words. I hadn’t asked for this, and wouldn’t have thought to. But in the seconds it took for me to get my brain around what he was offering, I realized that I actually did want to go back. It took me a moment to find my voice, and when I did, I simply said, “Thank you.”

The next afternoon everyone in our CODEL suited up again to fly out over the desert. The crew chief handed me a headset, so I could communicate with the crew while airborne. As we zipped along at 2,000 feet — much higher than I had flown during missions — we talked about the aircraft, just general chit-chat between fellow rotorheads. The Chinook has a loading ramp at the rear that can be opened in flight, for a fuller view of the ground. The crew chief dropped the rear hatch so I could see out, and I watched as the familiar dusty terrain zipped by underneath us.

And then I saw the trees.

We flew right over the palm grove, and suddenly I could see the small clearing that had saved Dan, Matt, Chris and me that day. The Black Hawk was long gone, having been blown up by U.S. forces after the shootdown so the enemy couldn’t make any use of it. There was nothing in the clearing but the tall grass — the last thing I’d seen before passing out that day. Our helicopter circled the field, and as we all looked down silently, I had a fleeting thought that my foot, or perhaps just the boot, might even still be down there somewhere. Sen. King snapped a photo of me, capturing that moment. I’m looking out the aircraft tail, lost in thought, wearing my prosthetic legs and holding a cane with my rebuilt arm. Though just a snapshot, it’s also something more: a portrait of the person I am today, looking back in time at the events that made me who I am.

This had been a heavy moment for everyone, so heading back to the base, I joked around with the crew. “Are you sure that was the right spot?” I asked. “Because I didn’t see my foot out there.” The guys laughed, but they obviously knew how much it meant to me that they’d taken me there. Later that day, they presented me with a left-foot boot, signed by the whole crew. “Sorry we didn’t find your boot, Ma’am,” one of them said as he handed it to me. “But here’s one for you to take home.”

The next day, with that boot safely packed into my suitcase, I rolled onto an aircraft and left Iraq, fulfilling the dream I’d nurtured since waking up in Walter Reed all those years ago. I had closed the circle, leaving on my own terms. But although this was the first time I’d left Iraq under my own power, it won’t be the last. I intend to keep going back, to work with the Iraqi people in hopes of rebuilding their country from the devastation of war. There’s a piece of me there, both literally and figuratively, a tie that will bind me to that country forever.

The boot that the crew gave me now sits on a shelf in my Senate office. When I look at it, I see a reminder not of what I lost in Iraq, but of what I gained from my experiences there. That boot represents the camaraderie, the mission, and the sense of purpose I share with my fellow Soldiers. It serves as a reminder that no matter how grievous the wound, healing is always possible, and that the lowest moments can lead to the greatest heights.

It reminds me that every day is, indeed, a gift.