Books |

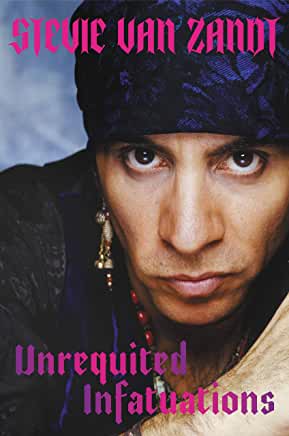

Stevie Van Zandt: Unrequited Infatuations: A Memoir

By

Published: Sep 27, 2021

Category:

Memoir

“February 8, 1964, there was not one single rock ‘n’ roll band in the country,” Stevie Van Zandt writes in his memoir. “February 9, the Beatles played The Ed Sullivan Show. “Goodbye school, grades, any thoughts of college, straight jobs, family unity and American monoculture.”

A year later, 15-year-old Stevie Van Zandt met Bruce Springsteen at a Jersey Shore battle of the bands. They both lived for rock ‘n roll. Eventually there was a band. Springsteen made some records.

“His first record did like ten thousand, second one did like twenty thousand, and they were just done with him — Bruce wasn’t gonna get a third shot. And somehow, by sheer willpower, that song got done: four or five months recording one song. Turned out to be worth it. They sent it out without the record company even knowing, and a couple of big rock stations picked up the song, the ‘Born to Run’ song.”

You may recall the simultaneous cover stories in Time and Newsweek. The sold-out arenas. “The Boss.” And Stevie was the guy in the headband who sang duets with Springsteen. What could go wrong? This: after co-producing “The River,” Van Zandt wanted to be more than a guitarist in the E Street Band. But there was only one Boss. In 1983 Van Zandt quit the band.

“Immediately upon working for fifteen years to make it, as soon as we make it, what do I do? I leave, right before the ‘Born in the U.S.A.’ tour. Everybody bought houses off that tour. I’m in Africa with an eleven-piece band that I’m paying for, using my little money to keep a band on the road talking about politics. I learned everything I know from leaving the E Street Band. And of course, one of the things I learned is, I never should have left. I ran out of money every year for the last thirty years.”

In his re-invention, “Little Steven” conceived and produced “Sun City,” the first celebrity (Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Miles Davis and Run DMC) protest anthem. “Pulling that off was beyond my celebrity status,” he says. “It was pure will power, which is one thing you can actually control.” The song and its effect launched his solo career, but his four solo albums didn’t chart.

Then, a miracle. David Chase invited Van Zandt to be a part of his new television show, “The Sopranos” — as Tony Soprano. Why? He wasn’t an actor. But Chase had seen him induct The Rascals into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he knew what he saw. HBO said, “No way.” So Chase hired him to play Silvio Dante, Tony’s consiglieri , which was pretty much what he’d been to Springsteen: “It was one of those stupid Hollywood stories that you wouldn’t believe if it didn’t happen to you. It was such a gift to have a whole new craft handed to me.” For a sample, watch this.

And then he returned to the E Street Band, scheduling his “Sopranos” shoots around tour dates. When “The Sopranos” ended in 2007, Van Zandt starred and executive produced “Lilyhammer” — watch the trailer — playing Frank Tagliano, a New York mobster who enters the Witness Protection Program and chooses to begin his new life in… Norway. He followed that with businesses, streaming radio, an annual cruise, and more It’s been a life-and-a-half, and I knew almost none of it. Time for a memoir. Like everything else he does, it’s first rate. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. For the audiobook, read by Van Zandt, click here.]

AN EXCERPT

Money and me, what can I say? We never got along too good. The pattern of my life is investing everything I have in what I believe in. Emotionally. All my time. All my talent. All my energy. And, yeah, usually all my money. Because I hate asking other people for money, and, until recently, never had anybody to do the asking for me. And we’ll see how long they last.

In 1982, I proceeded to spend what little money I had left after taking an eleven-piece band around the world for a year.

The Rock life isn’t for everybody. You’re basically packing your bags and unpacking them thirty years later. It’s a lifestyle that requires dedication, perseverance, patience, ambition, and, most of all, having no desire or ability to do anything else.

People are always saying, “Oh, how proud you must be! How righteous to have withstood the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune!”

But no. I’m sorry.

I resist all accusations of nobility. We were bums. Profoundly unsuited for any legitimate type of work. We did have honor for our outlaw profession. And a work ethic. I’ll give us that.

Part of the rationalization and satisfaction of being a boss working for another boss was the ability to offer suggestions and advice. I liked being the underboss in the E Street Band. The consigliere. It kept me out of the spotlight but allowed me to make a significant enough contribution to justify my own existence in my own mind. And there was a balance between me, Bruce, and Jon Landau. We had artistic theory and artistic practice covered.

But somewhere in ’82, it started to feel like Bruce had stopped listening. He had always been the most single-minded individual, with a natural extreme monogamy of focus in all things — in relationships, in songwriting, in guitar playing, in friends. Was that impulse now going to apply to his advisers?

At the time, I was hurt by the thought that maybe Jon resented my complete direct access to Bruce. I liked Jon a lot and thought he felt the same about me. If anything, I should have been the resentful one, but I wasn’t. In the end, I don’t think Jon had anything to do with the way things changed. There comes a time when people want to evolve without any baggage. To become something new and different without having to stay connected to the past.

This was, I think, one of those moments. Occasionally you need to be untethered. Without all this retrospective wisdom, though, Bruce and I had our first fight, one of only three we would have in our lives.

I felt I had been giving him nothing but good advice and had dedicated my whole life and career to him without asking for a thing. I felt I’d earned an official position in the decision-making process. He disagreed. So I quit.

Fifteen years. We finally made it. And I quit. The night before payday.

It was fucking with Destiny big-time. Or was it fulfilling it?

Briefly, let’s leave emotion out of it and examine the balance sheet of this rather . . . incredible move. On the positive side, I would write the music that would make up the bulk of my life’s work. Had I stayed, in between tours I probably would have produced other Artists. Or continued writing for others. Or both. But I probably would never have written for myself. I very possibly wouldn’t have gotten into politics. Would Mandela have gotten out of jail? Would the South African government have fallen? Probably. But we took years off both of those things.

I got to be in “The Sopranos” and “Lilyhammer.” They probably never would have happened. I would create two radio formats, a syndicated radio show, two channels of original content for Sirius (which has introduced over a thousand new bands that have nowhere else to go), a record company, and a music-history curriculum. Would any of that exist?

It would change Bruce’s personal life for the better; that’s indisputable. He would have been on the road for two years. Would he have had the time to hook up with Patti if she hadn’t been on the road with him? Would their three wonderful kids exist if I hadn’t left? Patti Scialfa would find the love of her life, a mixed bag for her well-deserved career — a more visible shortcut but forever in his shadow (welcome to the club) — and most importantly, again, would those same three amazing kids exist if she hadn’t joined the band to sing my vocal parts?

Nils Lofgren, hired to do my guitar parts, got a very rewarding second career, or third career if you count Crazy Horse, which he well deserved.

So some good things happened.

The negatives?

I lost my juice. As Chadwick Boseman, playing James Brown, says in the excellent biopic “Get on Up” after he fires his band, “Five minutes ago you were the baddest band in the land; now you’re nobody.”