Books |

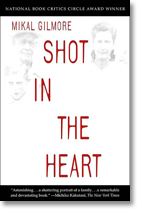

Shot in the Heart

Mikal Gilmore

By

Published: Mar 15, 2015

Category:

True Crime

So here we are in Utah. If I hadn’t thought of Gary Gilmore earlier, I can’t avoid him now; he’s in the news. Utah’s lawmakers are having the same trouble as other states with the death penalty: They can’t get chemicals to do the job efficiently and — the irony alone is killing — humanely. But they’re clever out here in Utah. They’ve found another way: They’re going to bring back the firing squad. And that made revisiting this extraordinary book inevitable.

Gary Gilmore. You vaguely recall: the tough-guy from Utah who shot and killed two Mormon men in the 1970s. Who was then sentenced to die by firing squad. Who, instead of fighting his execution, urged the state to go ahead. Whose last words were, reportedly, "Let’s do it." And who became the central figure of "The Executioner’s Song," a thick, riveting chronicle by Norman Mailer and, later, a TV movie starring Tommy Lee Jones.

That Gary Gilmore is not the Gary Gilmore you will meet here. This one is the brother of Mikal Gilmore, who grew up in the same household, took another path, and, somehow became a gifted writer, mostly for Rolling Stone. And who, nearly twenty years after his brother was executed, published a book about the man he knew.

"I have a story to tell," he says in the prologue. "It is the story of murders: murders of the flesh, and of the spirit; murders born of heartbreak, of hatred, of retribution. It is the story of where those murders begin, of how they take form and enter our actions, how they transform our lives, how their legacies spill into the world and the history around us. And it is a story of how the claims of violence and murder end — if, indeed, they ever end."

That is a terrifying story, for it reminds us that Gary Gilmore did not, one dark night, show up with a gun and a will to kill. Things happened along the way; he was molded into a killer. And those influences may go way back — to the very heart of his family. This is a story, then, of the origins of violence. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle download, click here.]

Mikal Gilmore looks for the decisive moment and finds, instead, links in a chain. There was the night in childhood when demons seemed to enter the house and hover over his mother and Gary — and from then on, Gary started having nightmares in which he was beheaded. There was child abuse, courtesy of their father: "We were late, we got in the door, we heard the door shut, and the next thing we knew we were getting razor-strapped across the back." There were shouting matches at dinner, and petty crimes committed on a dare, and then there was the Elvis Presley phase, with slicked hair and curled lips and a lot of attitude. And then, of course, the awful escalation.

In a book of chilling moments, two stand out. One occurs when during Mikal’s last visit to his brother. The night Gary was arrested, Mikal reminds him, he was on his way to the airport. Where was he headed? Gary tells Mikal he was on his way to Portland, Oregon — where Mikal was then living. Why? "I think I was coming to kill you," Gary says. "Do you understand why?" Mikal does: "I had escaped the family, or at least I thought I had. And Gary had not."

The other moment that will stay with me occurs just before Gary was executed. For his last words were not "Let’s do it." They were "There will always be a father."

The tragedy of losing people to violence is immense, and I do not want for an instant to slight the victims. But let us consider also — as this remarkable book does — that the killer was also a victim. And that this family produced four sons, none of whom became fathers.

In these pages, Mikal Gilmore delivers one of the greatest true-crime stories you’ll ever read. And more. By placing Gary’s tale in the arena of domestic tragedy and stripping all sensationalism from this story, he takes the story to another, deeper level — the book becomes a masterful study of child abuse and missed opportunities.

A prudent reader might conclude that crimes of great violence testify to the high cost of screwed-up childhoods. That reader might also conclude it’s much cheaper and wiser to reach out to our hurt, destructive children — to the kids we instinctively shun — when we can still connect with them rather than meet them, much later, at the point of a gun. As you give yourself over to this sad, sad story, do check your reactions and see, at the end, if you have become that prudent reader.