Books |

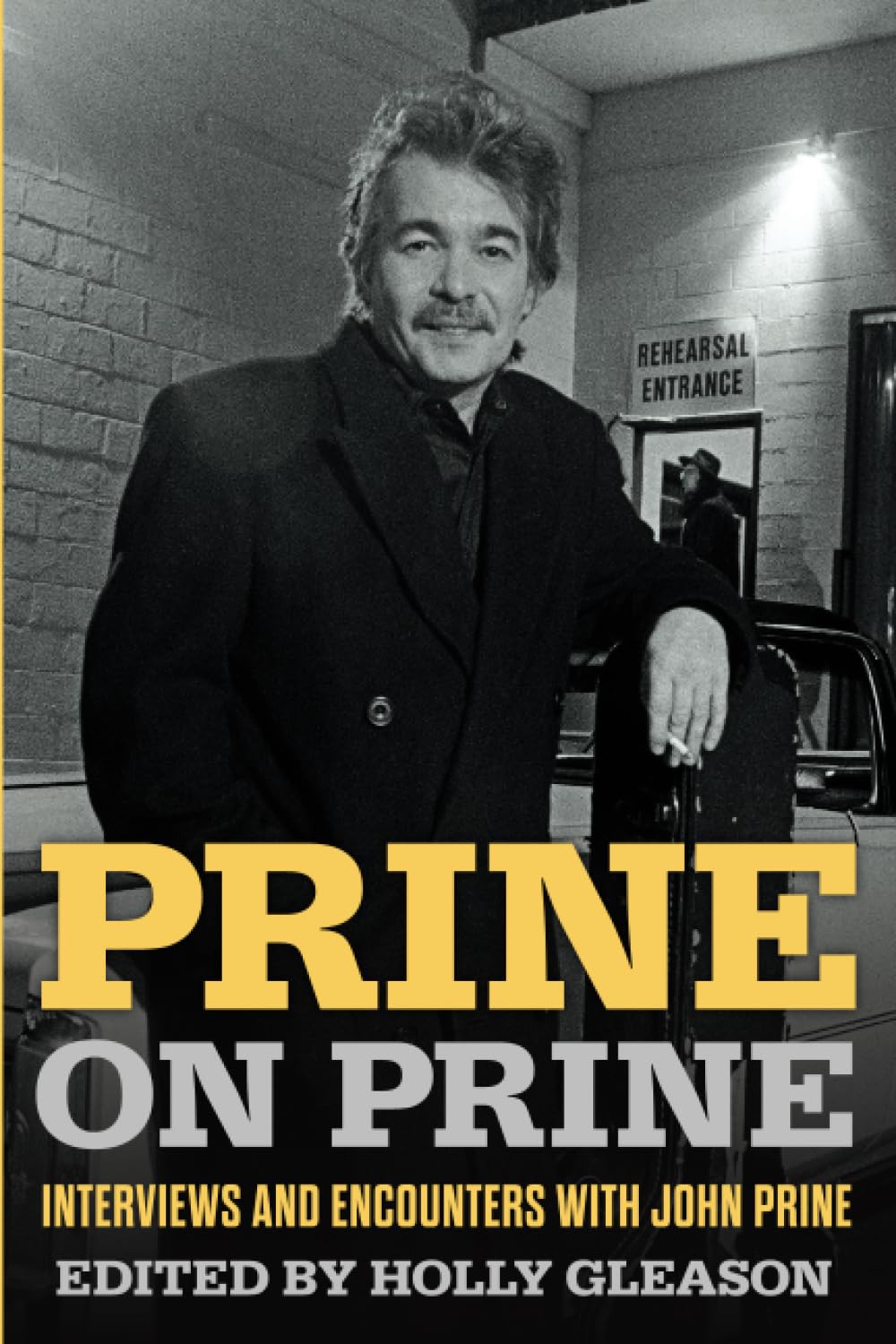

Prine on Prine: Interviews and Encounters with John Prine

Holly Gleason

By

Published: Sep 11, 2023

Category:

Entertainment

John Prine was hanging out at an open mic in a Chicago club, more or less minding his own business, maybe heckling just a little, when someone turned and asked if he thought he could do better. Prine was then a mailman, but he’d been writing songs since he was a teenager who stood in front of a mirror to see how he looked with a guitar, and now, at 23, he thought what the hell, and sang “Sam Stone” and “Angel from Montgomery.”

A few blocks away, Roger Ebert, film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, was watching a movie that was so bad he walked out and dropped into the music club for a beer. Though he had no history of covering music, he rushed to the office and wrote a review: “Prine appears on stage with such modesty he almost seems to be backing into the spotlight. He sings rather quietly, and his guitar work is good, but he doesn’t show off. He starts slow. But after a song or two, even the drunks in the room begin to listen to his lyrics. And then he has you.”

It was Prine’s first review. Steve Goodman brought Kris Kristofferson, who was also astonished: “It was like stumbling onto Dylan.” Two weeks after his open-mic debut, John Prine had a record contract. He quit his job, was nominated for a Grammy at 24, started a record company, and, for a half-century, was one of the most admired songwriters and performers in a genre notoriously unwelcoming to eccentrics and renegades.

Holly Gleason discovered John Prine when she was a 12-year-old kid in Cleveland listening to “Angel from Montgomery” on late-night radio. She wondered how a man could write a song from a middle-aged woman’s perspective about a dead-end marriage so intimately that she would have sworn Bonnie Raitt had written it. She devoured the music reviews of the Plain Dealer’s Jane Scott, but never dreamed of writing about musicians….until she had to pay for college. She was prolific, publishing music reviews and features at Black Miami Weekly, Country Song Round Up, and the Plain Dealer. Before she was 20, she was publishing three to five reviews a week for the Miami Herald. John Prine was to give a concert in South Florida. Holly Gleason was in South Florida. The assignment was hers.

That three-hour conversation was the start of a four-decade friendship. When COVID killed the 73-year-old Prine in 2020, it seemed obvious to Gleason — by then, a veteran journalist, publicist, and writer of “Better As a Memory,” a #1 country hit recorded by Kenny Chesney — that she should edit the Prine volume of the Chicago Review Press “Musicians in Their Own Words” series. Just published, “Prine on Prine: Interviews and Encounters with John Prine” is essential reading for anyone who’s been touched by his music. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

“Prine on Prine” follows the series format: the 40 best interviews and reviews by the best critics. Inevitably, it repeats — Prine’s story was so consistent that he told the same origin stories, with the same facts, no matter the year; he had no need to embellish them. Some go deeper — Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times, Dave Hoekstra of the Chicago Sun-Times, Mike Leonard at “The Today Show,” Jay Saporiti of The Aquarian, Lloyd Sachs’ No Depression cover story, and Gleason’s own contributions deliver the man inside.

It’s a surprise to read in those pieces that Prine, who often said he “just wanted to write and play songs” and didn’t seem driven — “No matter what time of day, he looks like he just rolled out of a deep sleep on a couch,” Michael McCall wrote in Nashville Scene — very badly wanted success for his music. He said he wrote best when he was cooking; the book includes his recipe for a wine-soaked pork roast. Although he sidestepped a crucial question — he said he liked “to let the character write the song” — he was fiercely committed to characters who are marginalized and ignored. The Vietnam vet with a needle in his arm, the woman who watches her life go by — these were his people and he wanted them seen. When Warner Brothers signed Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones and dropped Van Morrison and Bonnie Raitt on the same day, he was determined to start Oh Boy Records. “I figured if I was going to do it wrong,” he said, “I might as well do it wrong myself.”

Cameron Crowe, the Oscar-winning writer-director best known for “Almost Famous,” his autobiographical film about his teenage days at Rolling Stone, tells the story of an interview he and his sister did with Prine when he was still a teenager who needed his sister to drive him. Decades later, he ran into Prine at the Grammy Awards. He thanked Prine for giving him an interview all those years ago. He was sure Prine didn’t remember. “Of course I do,” Prine said. “Tell your sister I said hi.”

In piece after piece, Prine is delightfully original. When I interviewed him in 2005, HeadButler.com was so new we didn’t have much time, but he gave me fresh one-liners: “Books? I read ‘Archie and Veronica’ in the comic book form” and “I type so slow I can edit as I write.” He told Dave Cobb, on Sirius’ Outlaw show, that his favorite drink, the “Handsome Johnny,” calls for diet ginger ale, because “You don’t want to get diabetes from drinking.” He smoked a pack of Marlboros for 35 years, and paid for it with cancer. “When I see someone outside a restaurant about to light up, I’ll run over and stand next to them.” I don’t quite believe his explanation for all the songs of loneliness and sadness, but I’m charmed by it: “Usually when you’re happy, you don’t have time to write a song, ‘cause you’re enjoying your life. But when you’re not happy, you have all the time in the world to write.”

John Prine’s family came from Paradise, Kentucky. He wrote a song about a company that swept in and destroyed it. The company sued. The company lost. “Prine on Prine” is rich in improbable stories like that — stories that are like fables, but are, like the story of his discovery, verifiable. And, more often than not, uniquely joyful.