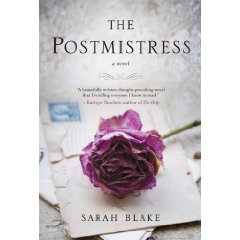

The Postmistress

Sarah Blake

By

Jesse Kornbluth

Published: Feb 08, 2010

Category:

Fiction

At dinner parties in New York this week, I anticipate three hot topics.

The policy wonks will spend a few minutes debating our government’s announcement that it has the right to kill Americans abroad, without any formal presentation of evidence, if they’re suspected of conspiring with terrorists.

More guests will spend a few minutes evaluating Sarah Palin as a Presidential candidate after she was caught with a cheat sheet on her palm with the answers to questions she knew she’d be asked.

Everyone will weigh in on the possibility that Sandra Bullock — Sandra Bullock! — will ace out Meryl Streep for the Best Actress Oscar.

And then it will be on to dishier topics….

So I was more than a little stunned, as I read the Manhattan dinner party scene that is the introductory chapter of The Postmistress, to discover that a guest could stop the room with this question: “What would you think of a postmistress who chose not to deliver the mail?”

Maybe New York was a simpler, starchier place when this dinner party was held — though it was, we learn, held in a decade when we had e-mail — but I find it hard to believe that a guest would respond to that question with a cry: “Don’t tell me any more — I’m hooked!” Others chime in: What if the letter contained a job offer? What was the motivation of the postmistress? “Monstrous,” someone opines. “Illegal,” another says.

Ridiculous, say I. Unreal. Happens only in novels about undelivered mail.

I’m a big believer in abandoning books if they begin badly. So why did I press on? Because the narrator of this chapter is Frances (Frankie) Bard, a journalist who has made a career of covering wars — and who worked for Edward R. Murrow in London during 1940 and 1941. An American woman as a correspondent during the Blitz: that’s golden material. I wanted to see if Sarah Blake was equal to it.

Here’s the good news: Blake gets London exactly right, and I gobbled every word about Frankie Bard’s exploits in England. She’s committed to her work, fearless in the face of nighttime bombings, and straight as a stick. (Murrow and pretty much every other correspondent, married or not, did what people do during wartime — that is, fuck like rabbits. In a year and a half, Frankie seems to have just one sexual encounter.)

But what makes Frankie a truly compelling character is that she wants to look hard at a story others shun — the German persecution of the Jews. She believes if she can just make those Jews real to American listeners, the United States will do something to intervene. Ah, the idealism of the young! Frankie’s reporting into a void — most of her listeners are praying that America won’t enter the war.

What does this have to do with the postmistress who withholds mail? Not much, and I wish you hadn’t asked. That postmistress, Iris James, lives at the tip of Cape Cod and presides over a post office only found in charming small towns — you know, shingles, wanted posters, a flagpole. The letter Iris holds on to was written by Will Fitch, a young doctor who grew up here. He’s just returned to town with his new and newly-pregnant wife, but, like Frankie, he’s an idealist — he’s off to London to offer his medical skills. Before he leaves, he gives Iris a letter and asks her to deliver it to his wife if… but you could write that scene yourself.

As luck would have it — and in novels, luck and destiny and gross improbability all merge — Frankie meets Will in a London bomb shelter. Let me not spoil what happens between them, but it’s big and meaningful, and it sends her, at book’s end, to Cape Cod, where Emma Fitch’s pregnancy is approaching critical mass.

Sarah Blake is married to a poet, and she has tendencies herself. Men defending London “go at their guns like drummers.” A sky is an “inconsolable” blue. The month of June “had opened her mouth wider and wider.” Laughter falls “like rain.” The late afternoon “sang.”

The language suggests this book is better than chick lit; it has aspirations to literary fiction. I once had a girlfriend with these ambitions. She’s quite well-known now. But not because she indulged her love of the poetic simile and the purple metaphor. In my view, she owes her career to an editor who told her, bluntly, “Don’t write. Just report.”

When Sarah Blake reports, “The Postmistress” is terrific. That is, when Frankie is working with Murrow. When Frankie is walking the streets of London by day or braving the German bombs by night. And, most of all, when Frankie takes a train across Europe, desperately recording the voices of the Jews, people who are alive now but who may not be later.

That’s not writing. It’s powerful reporting, and it is, I suspect, the reason Ms. Blake wrote the book. A missing letter? No big deal. The faces of thousands of condemned people who you might have some power to save? If you care, that matters. More than anything. Really, it’s all-consuming.

Inside “The Postmistress,” a great book is crying to get out. Enough of it made it that I couldn’t put it down.

To buy the Kindle edition of “The Postmistress” from Amazon.com,

click here.