Products |

NOVEMBER 4, 2020: Three stories for the day after the election

By

Published: Nov 04, 2020

Category:

editor's letter

Many of us went to bed – if we went to bed at all — wondering as much about this as about the outcome: How is it possible, after four years of this man, that more people voted for him than voted for him in 2016? It may yet happen that, as the polls suggested, “women will save us.” While we wait, three very short passages suggested themselves. All three have the same theme: compassion, concern for others, a willingness to consider a level of reality that’s beyond the world we see. So on a day when it’s hard not to button your coat against an ill wind and focus on you and yours, it may be useful to recall a foundation of most religions. “All the suffering there is in this world arises from wishing our self to be happy. All the happiness there is in this world arises from wishing others to be happy.”

—-

J.D Salinger had done his reading in religion. He’d done his spiritual homework. “The Catcher in the Rye” didn’t mean much to my daughter, and as I read it with her recently, it meant less to me. But some of the stories still matter to me, especially this passage.

The heart of “Zooey” is a long conversation about spirituality — about living correctly in a world that could care less. Zooey has this conversation with his mother while he’s in the bath, he has it with Franny as she sobs on the living room couch, and, finally, he goes into Buddy and Seymour’s old bedroom, picks up a phone that has not been used since Seymour’s death, and, pretending to be Buddy, calls Franny.

At the heart of this conversation is the passage which seemed way over the top in the 1960s and may seem overly sentimental to you now. It concerns “It’s a Wise Child,” the radio show that featured the oh-so-bright Glass kids. One week little Zooey didn’t want to go on. Seymour told Zooey he had to. And, as Zooey recalls, Seymour went on:

Seymour told me to shine my shoes…I was furious. The studio audience were all morons, the announcer was a moron, the sponsors were morons, and I just damn well wasn’t going to shine my shoes for them, I told Seymour. I said they couldn’t see them anyway, where we sat. He said to shine them anyway. He said to shine them for the Fat Lady. I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about, but he had a very Seymour look on his face, and so I did it. He never did tell me who the Fat Lady was, but I shined my shoes for the Fat Lady every time I ever went on the air again – all the years you and I were on the program together, if you remember. I don’t think I missed more than just a couple of times. This terribly clear, clear picture of the Fat Lady formed in my mind. I had her sitting on this porch all day, swatting flies, with her radio going full-blast from morning till night. I figured the heat was terrible, and she probably had cancer, and – I don’t know. Anyway, it seemed goddam clear why Seymour wanted me to shine my shoes when I went on the air. It made sense.

—-

This is a sliver of a scene from my novel-in-progress. Billy DeVito is 14, a boy with special gifts. Benji is his smart friend from school. Benji is Jewish, Billy isn’t. But Billy is curious about religion, and one Friday night, he goes to synagogue with Benji. Walking home, they have one of those deep, meaningful conversations kids used to have and may still do. (FYI: the pronunciation is “Lam Ed Vav.”)

“The 36 Lamed Vavs are the most important people in the world,” Benji said. “Literally, they keep it going, and if even one of them disappears, the world will end. We don’t know who they are — if someone claims he’s one of the Lamed Vav, that automatically means he’s not. But what’s really amazing is that the Lamed Vavs don’t know they’re Lamed Vavs. It’s like they’re walking down the street and they see someone suffering and they kind of inhale the trouble, and… poof… it’s gone, and they go back to their lives.”

“So how do we know about them?”

“There are stories.”

“Know any?”

“I read a book.”

“If they’re unknown…”

“The stories are second-hand. This is my favorite: “A man comes to the rabbi to beg for the life of his sick son. The rabbi goes out and finds the ten biggest thieves in the city. The rabbi’s friends ask why he didn’t ask decent men to help with the healing. Why ten criminals? The rabbi explained, ’I saw all the Gates were not only closed to this boy, they were locked. So I needed ten thieves to pick the locks… to break open the Gates of Heaven.’”

“The boy was healed?”

“Even before his father arrived home.”

Billy, thinking logically: “The rabbi made a miracle. He blew his cover.”

Benji, exasperated: “No. The rabbi was a miracle. But yes, okay, the stories are usually about people no one notices — bus drivers, garbage men, the bum on the corner. And that’s the coolest thing about them. They’re God’s reminder that we should treat everyone with dignity and respect. Because you just never know.”

—-

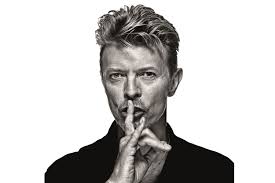

THIS IS NOT A STORY DAVID BOWIE TOLD ME, though I interviewed him and we swapped a few. This a story NEIL GAIMAN tells….

My friend told me a story he hadn’t told anyone for years. When he used to tell it years ago people would laugh and say, ‘Who’d believe that? How can that be true? That’s daft.’ So he didn’t tell it again for ages. But for some reason, last night, he knew it would be just the kind of story I would love.

When he was a kid, he said, they didn’t use the word autism, they just said ‘shy’, or ‘isn’t very good at being around strangers or lots of people.’ But that’s what he was, and is, and he doesn’t mind telling anyone. It’s just a matter of fact with him, and sometimes it makes him sound a little and act different, but that’s okay.

Anyway, when he was a kid it was the middle of the 1980s and they were still saying ‘shy’ or ‘withdrawn’ rather than ‘autistic’. He went to London with his mother to see a special screening of a new film he really loved. He must have won a competition or something, I think. Some of the details he can’t quite remember, but he thinks it must have been London they went to, and the film…! Well, the film is one of my all-time favorites, too. It’s a dark, mysterious fantasy movie. Every single frame is crammed with puppets and goblins. There are silly songs and a goblin king who wears clingy silver tights and who kidnaps a baby and this is what kickstarts the whole adventure.

It was ‘Labyrinth,’ of course, and the star was David Bowie, and he was there to meet the children who had come to see this special screening.

‘I met David Bowie once,’ was the thing that my friend said, that caught my attention.

‘You did? When was this?’ I was amazed, and surprised, too, at the casual way he brought this revelation out. Almost anyone else I know would have told the tale a million times already.

He seemed surprised I would want to know, and he told me the whole thing, all out of order, and I eked the details out of him.

He told the story as if it was he’d been on an adventure back then, and he wasn’t quite allowed to tell the story. Like there was a pact, or a magic spell surrounding it. As if something profound and peculiar would occur if he broke the confidence.

It was thirty years ago and all us kids who’d loved “Labyrinth” then, and who still love it now, are all middle-aged. Saddest of all, the Goblin King is dead. Does the magic still exist?

I asked him what happened on his adventure.

‘I was withdrawn, more withdrawn than the other kids. We all got a signed poster. Because I was so shy, they put me in a separate room, to one side, and so I got to meet him alone. He’d heard I was shy and it was his idea. He spent thirty minutes with me.

‘He gave me this mask. This one. Look.

‘He said: ‘This is an invisible mask, you see?

‘He took it off his own face and looked around like he was scared and uncomfortable all of a sudden. He passed me his invisible mask. ‘Put it on,’ he told me. ‘It’s magic.’

‘And so I did.

‘Then he told me, ‘I always feel afraid, just the same as you. But I wear this mask every single day. And it doesn’t take the fear away, but it makes it feel a bit better. I feel brave enough then to face the whole world and all the people. And now you will, too.

‘I sat there in his magic mask, looking through the eyes at David Bowie and it was true, I did feel better.

‘Then I watched as he made another magic mask. He spun it out of thin air, out of nothing at all. He finished it and smiled and then he put it on. And he looked so relieved and pleased. He smiled at me.

‘’Now we’ve both got invisible masks. We can both see through them perfectly well and no one would know we’re even wearing them,’ he said.

‘So, I felt incredibly comfortable. It was the first time I felt safe in my whole life.

‘It was magic. He was a wizard. He was a goblin king, grinning at me.

‘I still keep the mask, of course. This is it, now. Look.’

I kept asking my friend questions, amazed by his story. I loved it and wanted all the details. How many other kids? Did they have puppets from the film there, as well? What was David Bowie wearing? I imagined him in his lilac suit from Live Aid. Or maybe he was dressed as the Goblin King in lacy ruffles and cobwebs and glitter.

What was the last thing he said to you, when you had to say goodbye?

‘David Bowie said, ‘I’m always afraid as well. But this is how you can feel brave in the world.’