Books |

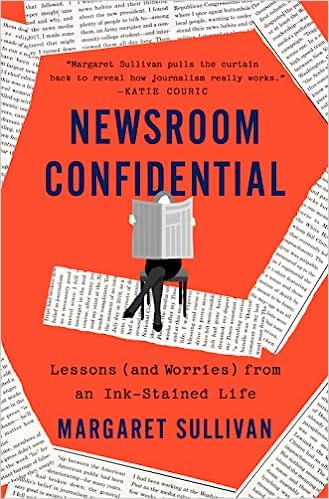

Newsroom Confidential: Lessons (and Worries) from an Ink-Stained Life

Margaret Sullivan

By

Published: Oct 18, 2022

Category:

Memoir

I thought Life, by Keith Richards (with a lot of help), was the best rock memoir I ever read right up to the minute the Rolling Stones were officially anointed as the world’s greatest rock band. After that, it held few surprises — there’s no story as undramatic as a success story when there’s no longer any risk or reason to change or looming failure.

Why is Act One considered, by nearly universal acclaim, the greatest theatrical memoir ever written? Because it ends just as Moss Hart scored his first Broadway success. He never wrote “Act Two.” Just as well. It would have been about fame and fortune, which was so massive in his case that he bought a country house and built additions that, as Alexander Woollcott remarked, were “just what God would have done if He had the money.”

Margaret Sullivan’s memoir is two books, but they’re not “before” and “after.” One is the story of a girl from Buffalo who ran toward a future that was, she sensed, somehow built on words — it’s a love story. The other is a manifesto by the former Public Editor of The New York Times about the threat to democracy in America and what the press might do to chronicle and neutralize it. Do I need to say that everything I have read about this book is about the press — not surprising, because the press is endlessly fascinated with itself. (For example, the headline of the Times review says it all: “A Veteran Press Critic Wants Her Profession to Defend Democracy.”) Sullivan’s manifesto is passionate and urgent. But it’s not new.

The reason to read the book — the reason that parents might want to share it with their daughters- — is for the memoir, the story of a supremely talented young woman making her way in a business as misogynistic as the executive office of a professional football team. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

When she was ten, “my father handed me a blank 1968 datebook that I decided to use as a diary.” As a teenager, her heartthrobs were Bernstein and Woodward. She became the editor of her high-school paper. She read the daily newspaper, “at least taking in the headlines.” In college, she wrote for the newspaper.

I cheered her on when she resisted the dominant message of that time: girls should marry young and have children immediately. If a young woman started a career and became successful, it shouldn’t last long. (At 30, Sullivan’s mother quit her job as a fashion buyer, with buying trips to Paris and Milan on her schedule, to marry and start a family.) But journalism was Sullivan’s “obsession,” and after scoring close to perfect grades at a small Jesuit college in Syracuse, she transferred to Georgetown. She won a summer internship at The Niagara Gazette, where she wrote stories and was offered a fulltime job. She wanted to be better prepared, so she accepted a scholarship at the Medill School at Northwestern. And then she began her career as a reporter for the Buffalo Evening News.

“By the end of the 1980s, I had been named an assistant city editor, supervising a six-man (yes, all male) team of politics and government reporters.” Stressful? Yes. But “we worked it out.” Buried in that paragraph are stories I can only guess at.

She became editor of the Buffalo News in 1999. She notes that her husband was the editor of the paper’s Sunday magazine. He suddenly found himself reporting to his wife. She doesn’t say why they divorced, though I can guess, and she’s silent about what it was like to be the mother of two children while the newspaper business was starting its decline. And while I cheered when, in 2012, she became the Public Editor of the Times — in essence, the columnist/ombudswoman whose boss was the paper’s readers — I soon understood why the job was nonstop challenges. “Over nearly four years in the job, I never had a completely comfortable day as public editor,” she writes, and the stories of our greatest paper’s errors make that an understatement. [To read an excerpt from the book about the “many strange chapters” of the paper’s coverage of the 2016 Democratic nominee, click here.]

In 2016, having served longer than any Public Editor at the Times, she moved on to the Washington Post, where her writing was housed in the Style section. Jobs like hers, she believed, have “term limits,” and this year she became a visiting professor at Duke.

Since 2016, she has written, “journalists have been struggling to adapt.” Not exactly. As the spate of books about the Trump years illustrates, journalists have successfully stifled the impulse to publish stories that matter when they could make a difference — they hold stories back until their books are published. Sullivan, in stark contrast, honors the moment in the moment. 141,000 people follow her on Twitter: @Sulliview. You are advised to join them.