Books |

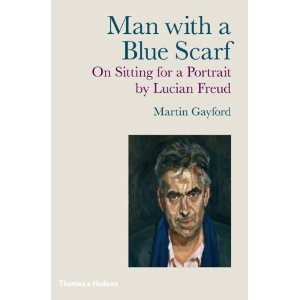

Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud

Martin Gayford

By

Published: Jul 27, 2011

Category:

Art and Photography

Guest Butler Jane Chafin is director of the Offramp Gallery in Pasadena, California. A former painter, she has worked as a registrar at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery and written for the Los Angeles Times.

“Man with a Blue Scarf: On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud” gives unprecedented access into the otherwise private realm of Freud’s studio, and a look at the slow, deliberate process of painting. From November 2003 through July 2004, art critic Martin Gayford sat for his portrait. He spent those 49 sessions — at least 150 hours — in the same position, with his right leg crossed over his left, wearing the same clothes, bathed in the same pool of light in the darkened studio, sometimes in silence, sometimes in dialogue with the 83 year-old Freud. He kept a diary as they went along, recording bits of conversation, thoughts and observations. It is from this diary that he has crafted this charming and revelatory book. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here.]

What struck me most about the book was the insight into Freud’s process — specifically, how slowly and intentionally he paints and how that would seem to contradict his broad, spontaneous-looking brushstrokes. The portrait in this case starts with a quick charcoal sketch on canvas, over which Freud begins applying paint to the area between the sitter’s eyes, working slowly out in all directions, leaving parts of the white canvas unpainted almost until the very end. Intense concentration and looking precede each brush stroke, and often the stroke is "practiced" by tracing it in the air with his arm. Once on the canvas, if the stroke isn’t exactly right, it is wiped off and the process begins again.