Books |

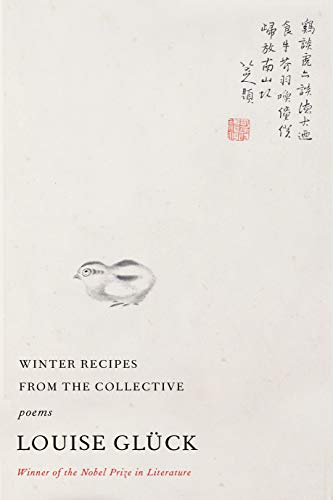

Louise Glück: Winter Recipes from the Collective

By

Published: Dec 20, 2021

Category:

Poetry

The best book of short stories I read this year is Louise Glück’s book of poems, “Winter Recipes from the Collective.” 15 poems. 64 pages. And no “poetic” language — most of those poems are narratives, characters telling stories in language that stings and bites. It’s perhaps not just anecdotal that her father was one of the inventors of the X-Acto knife.

This is Glück’s first book since she won the Nobel Prize. Her comments on that honor suggest that it’s less meaningful than her age, which is 78. It’s always dangerous to think that a narrative poem is the disguised voice of the poet, but it’s not hard to see that a number of these poems explore a common theme: time, endings, death. Don’t be put off by the seriousness of those subjects. If you are old enough to be aware that time is moving faster than ever and that the supply of sand in the hourglass isn’t infinite — if, say, you’re smart and 40+ — you’ll read attentively, for these poems are pure protein.

The first poem announces the theme. “Day and night come/ hand in hand like a boy and a girl.” They climb a mountain. The narrator and her companion — her lover, I believe — climb the same mountain. “I say a prayer for the wind to lift us.” The prayer has no effect. The wind takes them downward. She offers words of comfort, “but words are not the answer.” Then they’re “simply falling…” They see the boy and girl. They’re standing on a wooden bridge. The narrator can see their house behind them.

How fast you go they call to us;

But no, the wind is in our ears,

That is what we hear—

And then we are simply falling —

And the world goes by,

All the worlds, each more beautiful than the last;

I touch your cheek to protect you —

A short story? More like a sequence in a movie. Read the words, see the film: that’s the way I love to write and the way I like to read. I look for writing of that apparent clarity everywhere. I see it far too rarely.

The next poem is a travel diary: “I had left my passport at an inn we stayed at for a night or so/whose name I couldn’t remember. This is how it began.” Better believe that passport has a story, and it’s life-changing with a breathtaking efficiency.

In the title poem, old men go into the woods to gather the moss that will be a staple of the collective’s diet in winter. It’s nutritious, but not tasty — it’s “like matzoh in the desert.” The recipes? They’re “only for winter, when life is hard. In spring, anyone can make a fine meal.”

Glück’s greatest strength is her ability to tap into common feelings. She writes a line, and you say to yourself: I’ve had that thought. Like this: The world is beautiful, and we have to love it, and — here comes the twist — our appreciation of that beauty and our willingness to feel that love offer us no protection against… falling. What do we know? Not much: “Who can speak of the future? Nobody knows anything about the future, even the planets do not know.” And yet we must live. More correctly: we must have the courage to live.

The concierge, I realized, had been standing beside me.

Do not be sad, he said. You have begun your own journey,

not into the world, like your friend’s, but into yourself and your memories.

As they fall away, perhaps you will attain

that enviable emptiness into which

all things flow, like the empty cup in the Daodejing—

Everything is change, he said, and everything is connected.

Also everything returns, but what returns is not

what went away—”

I’ll be thinking about that last line and that story — excuse me, that poem — like it’s a koan I’ve been assigned to crack. And pleased, in the midst of the noise of the day, to have that idea, and these stories — excuse me, these poems — to think about. Reading this book gives me great comfort. And will again. I hope that happens for you.

[To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]