Music |

Lou Reed (1942-2013)

By

Published: Oct 28, 2013

Category:

Rock

Guest Butler Holly Gleason is the first friend I made in Nashville, too many years ago to count. Lucky me: she knows everybody and everything. Her first identity is as a pop culture critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Oxford American, Rolling Stone, Musician, Paste, and every music journal of note. She has co-written a #1 song and is finishing her first novel. She’s also a sought-after artist development consultant based in Nashville and Palm Beach. Find more of her writing here.

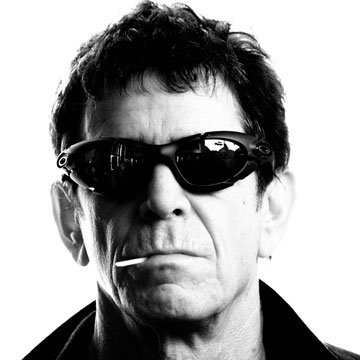

“Sweet Jane” and “Waitin’ On the Man,” “Heroin” and “Rock & Roll,” the Velvet Underground, Nico, nihilism and Andy Warhol. Black leather. Razor thin. Whip smart. Hard, uncaring. Behind those mirrored sunglasses, David Bowie wanted to be him.

Talk about capturing the imagination.

In a fancy conference room at Warner Brothers, the famously caustic Lou Reed took one look at me, blinked twice, listened to my question about metaphor and elegy, the way his downtown realm’s gory fabulousness was being paved over and washed away, then stood without a word and… left!

The Warner publicist walked in, bottle of water in hand, to see an empty chair and a stunned young woman. He could only ask, “Where’s Lou?”

“I don’t… know…I… uh… asked a question… and…”

Turning on his heel, the publicist was gone. I sat uncomfortably, uttering “WTF,” the mantra of stunned journalists everywhere.

In what was a matter of minutes, but felt like an hour, the door opened. Reed walked in, black t-shirt slack against his lean, sinewy body, and took his chair. Nothing was said. Nothing was acknowledged. He just started talking about gentrification, the city of New York having been wild and now becoming constricted, about being lost in the gutter and feeling like you can see the sky.

I didn’t ask many questions. Honestly, I was shaking and trying to not cry. He was intense and scary and everything you’d fear. Though now, he was just a guy, talking about a record, trying to invest enough truth without denting his soul or puncturing the things he wanted to keep for himself.

“Lou really liked you,” the publicist said the next day. “He thinks you’re smart.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Awesome.”

It was always something with Lou Reed. He was raw, nerve-wracking, even mean. But you couldn’t turn away, couldn’t escape what had engaged, most likely disturbed you.

So I kept watching, asking Lou questions when I could.

HITS magazine gave me access for a no-incident phoner, the kind of quick and dirty festival of calls that artists make to pimp the product. No revelations, no big bombshells. It was so clean and clinical, it was almost a letdown.

Years later, Lou Reed, with his mascara, rejectionist mantle and references to angel dust and turning tricks, appeared to be mellowing. Indeed, he seemed the underworld’s eminence of Manhattan. [To buy a MP3 of Lou Reed’s 31 best songs, click here.]

My final opportunity to speak with him came four falls ago. On a beautiful day in the Village, at a fancy French bistro that was anything like the squalor his post-Velvet Underground phoenix had risen from. Or maybe just like it, because while Warhol was intrigued by slumming, he was even more taken by the luxe. [To buy the CD of ‘The Velvet Underground & Nico,’ click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

Ordering for both of us, he opened the conversation with the challenge of just why American Songwriter would want to interview him now.

Fully grown, I’m used to artist tantrums and meltdowns. I smiled, wrinkled my nose and leaned back across the white linen-dressed table with the pretty flatware and returned, “Why, Lou, how dare you? How many times have you turned them down is more like it? You are impossibly to talk to, deny everyone and don’t entertain genius, let alone fools.” And then, laughing: “Shame on you. Shame, shame.”

With his rat terrier curled at his feet, he knitted his brows and puckered his lips. The once sinewy body was looking more like the Social Securitarian on Miami Beach in the ‘80s. Gone was the coiled whip tautness. I almost felt bad.

Lou liked to start with people like me by creating a rift; he figured by launching a salvo early he could have the dynamic he wanted. He hadn’t banked on the impact of our first dance or the passage of years and experience. His master plan was not working.

Instead, we talked and talked and talked. About literature, about inspiration, about motivation, about life. At the crux of the conversation was the reissue of “Berlin,” the chaotic, nervy concept project that followed his breakthrough genderbenderdefender “Transformer,” produced by Bowie at the height of his Ziggy Stardust zeitgeist. “Transformer” contained the disco/downtown anthem “Walk on the Wild Side.” It launched a superstar. [To buy the CD of ‘Transformer,’ click here. For the MP3 download, click here.]

Who then committed commercial suicide.

Or as the conversation went:

“When you made ‘Berlin,’ you’d made ‘Transformer… that’s some transition.”

“Yes, the worst thing anyone has ever thought of doing.”

“Then why did you do it? Such a hard left. It was brave…”

“Not really. That’s the last thing I’d say. That’s what got written, so that was that. That was what was there. I’m happy to get any idea about anything. It’s so hard.”

So hard. Or not. Or maybe. That’s the reality of the non-negotiable Lou Reed. He was brittle, unyielding, yet quick to give once he decided you were worthy. Inscrutable, perhaps as a defense. And in this, his last incarnation, almost accessible.

Indeed, there I was in lower Manhattan, watching him indulge the people strolling by after their double takes and the double back to have “their moment with Lou Reed.” You’d expect he’d chew their faces off; he couldn’t have been more gracious.

As the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame’s leading cantanker, Lou’s bitchiness wrought its own kind of respect. It imbued the music with that cutthroat anarchism, an acid burn without mercy. That makes it easy to forget his own roots were in doo-wop. He was a romantic at heart, callous though he came off. Those shredding rockers and dour minor key slow ones? Those songs were steeped in the yearning of one who says he don’t give a damn because he can’t possibly show you how he really feels.

That was the crucial irony. Talking about his little dog, his tai chi teacher, the mentor who read him “Finnegan’s Wake,” there was no camouflaging that tender heart. Ahhhh, the rat bastard of rock & roll: in the end, just one more tramped soul yearning to kick out whatever stood between him and the vulnerability that lay inside.

For Lou Reed’s last interview with Holly Gleason, click here.

BONUS VIDEO