Books |

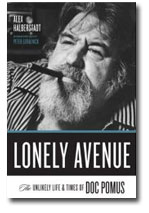

Lonely Avenue: The Unlikely Life And Times of Doc Pomus

Alex Halberstadt

By

Published: Jul 10, 2023

Category:

Biography

He was short and stubby. He’d had polio at 9; he couldn’t walk without braces and crutches. To see this 16-year-old kid struggle to the stage of a Greenwich Village club in 1943 was to get a taste of what it was like to run into Toulouse Lautrec in a Paris cafe half a century earlier — you knew this guy was….different.

His dreams, for starters. Jerome Felder wanted to stand in a boxing ring and, though he couldn’t move, win the championship. Or fire unhittable fastballs from the pitcher’s mound. And the women — they’d be lined up for him.

In that club, though, Jerome connected with a dream that could come true. He got on stage and sang the only blues song he knew — and people clapped. The next night, he was back, with a new confidence and a new name: Doc Pomus. He was on his way to becoming the greatest songwriter in the history of early rock ‘n roll.

There are books you read because you’re interested in the subject. And then there are books you read because you just happened to pick them up — and the next thing you knew, your mouth was dry, your heart was racing, and you were turning the pages like the secret of life lay just ahead. “Lonely Avenue” was like that for me: a freight train with no brakes, bound for glory and ruin.

I have a soft spot for stories about people who make something out of nothing — people who reach into their guts and share their deepest, rawest feelings in a form that makes us feel them too. The Doc Pomus story is the very best of that breed. A Brooklyn kid who didn’t want to waste his life at a desk. A misfit who found his first home in black blues clubs. A survivor who realized he was never going to make it as a performer and started writing songs because behind-the-scenes was the closest a white, chunky cripple could come to touching an audience.

He was in his 30s when he teamed up with an 18-year-old composer named Mort Shuman. And when, unaccountably, he persuaded a virginal blond actress to marry him. A few years later, he chanced upon their wedding invitation, and he remembered what it was like to sit on the sidelines while other men danced with his wife. He picked up a pen and watched the words flow:

You can dance

Every dance with the guy

Who gives you the eye

Let him hold you tight

You can smile

Every smile for the man who held your hand

‘Neath the pale moonlight

But don’t forget who’s taking you home

And in whose arms you’re gonna be

So darlin’, save the last dance for me…

Before Ben E. King recorded that song, Ahmet Ertegun told him the back story. King’s eyes misted. And, as you know, he and the Drifters delivered a record they’ll be playing as long as there are lovers. Watch the video.

Silly stuff followed. “Turn Me Loose” and other hits for Fabian, a teen idol “who had a reliable range of four or five notes.” But also, more hits for Ben E. King and the Drifters: “This Magic Moment” and “I Count the Tears.” For Dion & the Belmonts, “Teenager in Love.”And, for Elvis, “Suspicion” and “Viva Las Vegas.”

If this were just a story about music, it would be fascinating — Halberstadt introduces us to a world of sleazy promoters, crooked producers, random hangers-on and freaks. All inhabited Doc’s world — he was not only the ultimate hipster, the insider’s insider, but he had infinite time for stories. To read these pages is to enlarge your world. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here. To buy a great CD, “Till the Night is Gone: Tribute to Doc Pomus,” click here]

And then, to read these pages is to watch a world explode and one of its kings have to re-invent himself. What happened? The Beatles. The Stones. And Dylan. “Tin Pan Alley is dead,” Dylan announced. “I killed it.”

At 40, Doc Pomus was broke again. His weight ballooned to 350 and crutches were out of the question — now he was chair-bound. His wife divorced him and took the kids. This is where the Doc Pomus story gets really exciting for me, because it’s one thing to be at the bottom when you’ve never seen the top, another to wake up in a fleabag hotel after you’ve known success. Anyone who’s been there will tell you: It’s harder to make it the second time.

Pomus made it twice. That’s one good reason to read this book: as a fable of disability denied, as the rugged, raw story of a guy in a wheelchair learning how to become the tallest guy in the room. A large claim, but here it is: the story of a great 20th century artist.