Movies |

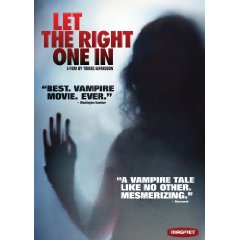

Let the Right One In

By

Published: Aug 17, 2009

Category:

Drama

What an amazing, strange and tender love story — and, yes, I’m talking about the Swedish vampire movie Let the Right One In. It’s out on DVD in the United States, and the first thing to say about it is that the movie company apparently wouldn’t pay for a quality translation; the subtitles here are crude and inaccurate. In most films, this would be fatal. Luckily, there’s very little talking in the first place.

And, in this case, there is something to be gained in just looking at this movie with no sound at all. (Oddly, this is the way I actually remember it from the first time I saw it.) In some ways – particularly because of the repeating shot of the exterior of the apartment complex the principals live in – it reminded me of Kieślowski’s Decalogue. And there’s that same extraordinary bleakness made of the night (day only comes in flashes) and snow (especially snow).

The movie is about Eli, a 12-year old girl vampire (and as androgynous a vampire as a horror flick can allow) who falls in love with Oskar, the blond dreamer who is the prime target of the bullies at school. Oskar lives with his mother in the creepy complex and lives with his father (vaguely gay) on what we can only assume are the weekends (every day in this movie feels the same) in a place where the snow is a lot more fun.

Oskar lives with his mother in the creepy complex and lives with his father (vaguely gay) on what we can only assume are the weekends (every day in this movie feels the same) in a place where the snow is a lot more fun. He’s quiet and unreadable, so he’s everybody’s screen to project all that youthful angst upon.

Eli lives with someone like a father, though we’re never really sure what the relationship is here because from the beginning we sense “father” is on a mission. That mission, as it turns out, is to kill people, hang them upside down and drain their blood so that Eli can eat/live. Eventually – and importantly – Eli has to fend for herself and Oskar is slowly made full aware of the extraordinary and complex and truly creepy world he has entered.

The wonderful surprise here is that the vampire world here isn’t weird or complex to Oskar because Eli and Oskar love each other unconditionally. In this movie, childhood is replaced by vampirehood which becomes, as the film moves forward, a surrealistic way to describe being a child in which innocence doesn’t come with the experience; a childhood beyond childhood, like the one being lived by the feral child in Truffaut’s "The Wild Child". The vampire is a citizen, not an outcast. Oskar’s love for Eli isn’t based on what Eli does but on who she is: the old soul who seems to be going on 12 year after year after year.

The extraordinary thing about the movie is that the horror is muffled, neutralized, so that every bloody and terrible encounter (and they are here – this is a horror movie) is flat and almost ordinary with the rhythm (each murder languors) more suited for a sleepwalker than a killer. It creates an alternate universe that the people here actually want to live in.

— Guest Butler Michael Klein is the author of "1990" (a book of poems), "Track Conditions" (a memoir) and "The End of Being Known” (essays). He can be reached at michaelklein255@me.com.