Movies |

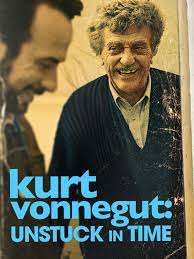

Kurt Vonnegut: Unstuck in Time

directed by Bon Weide and Don Argott

By

Published: Dec 08, 2021

Category:

Documentary

I met Kurt Vonnegut on May Day, 1969. Ray Mungo, the proprietor of Total Loss Farm, had invited Kurt up for the festivities, and Kurt and his wife Jane had driven from their home on the Cape to spend the day on a hippie farm. They got quite a show. Many communards were on LSD, some naked; there was cheerful chaos in the air. I recall Jane leaning against their car, weeping. Kurt seemed distantly removed. For one thing, he’d seen worse. For another, Slaughterhouse-Five had just been published, and the worst he had endured was finally behind him, at least on paper.

Jump ahead to 1982. Robert Weide was 23, a beginning filmmaker, and deep in the cult of Vonnegut. Weide wrote Vonnegut: “He wrote me back, which was shocking to me, and gave me his phone number and welcomed me to call him, which I did. We got together the next time I was in New York, which was later that year, and we hit it off.”

And now, after 40 years of intermittent filming, there’s a movie. [To stream it on Amazon Prime, click here.]

The film has many strengths, it’s possible there are many more in the footage that Weide and Don Argott, his co-director, shot over the years. Weide elected to make a different film: a celebration of their friendship. It’s intermittently interesting, but let’s be honest — you didn’t rent this film to meet Bob Weide. The Times critic is brutal on this point:

“I didn’t even want to be in this film in the first place,” Weide, who’s helmed documentaries and several seasons of “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” tells the camera, sounding slightly disingenuous. Not being in a movie can be the easiest thing in the world, if you put your mind to it.

The value is Kurt, and his struggle not to succumb to one tragedy after another. He was lucky in this: he found his calling young.

Shortridge High School in Indianapolis, Indiana, had a daily paper. I learned to write for peers. It was a swell experience for me because I learned to write journalistic style, which was to be clear and don’t bluff and also to say as much as possible as quickly as possible. And my books are essentially that way. I give away the big secrets in the first page and tell people what’s going to happen.

In 1943, his mother committed suicide.

It was Mother’s Day. My sister and I found her. It was upstairs. Indeed, she was dead. It was a Marilyn Monroe thing. It was a combination of pills and alcohol; a lot of pills.

A year later, he was captured in the Battle of the Bulge. As a prisoner of war, he was living in an underground meat locker in Dresden. Over two days in 1945, the British and American air force dropped 3,900 tons of bombs and incendiary devices on the city. Almost 25,000 people died. When the bombing ended, Vonnegut and his fellow prisoners emerged from underground. Their assignment: burning the bodies.

Vonnegut, speaking to Weide: “The dogs in my neighborhood where I was growing up had more to do with shaping my character than anything that happened during the war.”

Vonnegut’s daughter: “He’s in denial.” At the least — this is a galactic case of PTSD. And there was more to come. In 1958 his beloved sister Alice died of breast cancer a few days after her husband drowned in a train accident. And although he was raising a family and making a living and writing, there was a dark cloud over him that looked as if it would be his lifelong companion.

And then he wrote “Slaughterhouse-Five.” (The title is the German name for his prisoner of war address: Schlachthof-fünf.) And suddenly he was famous, and loved by more than high school and college kids. From a perceptive essay by Steve Almond: “In his books, he performed the greatest feat of alchemy known to man: the conversion of grief into laughter by means of courageous imagination. Like any decent parent, he had made the astonishing sorrow of the examined life bearable.”

Yes, astonishing. I always felt Kurt was fundamentally lonely. But he created his own culture: people lonely together. His books were touchstones. He took the worst that life can deliver and achieved a kind of perspective.

In the movie, he says: “When things are going sweetly and peacefully, please pause a moment and then say out loud, if this isn’t nice, what is?”

It’s worth watching the film just for that.