Books |

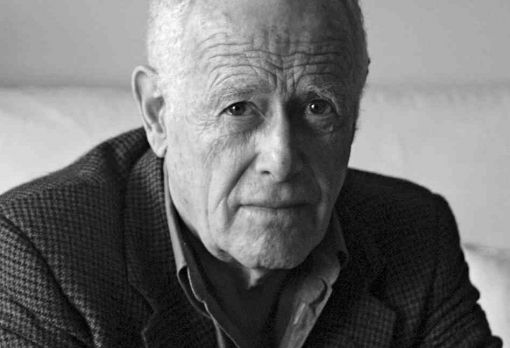

James Salter (June 10, 1925 – June 19, 2015)

By

Published: Jun 20, 2015

Category:

Fiction

Acorns do not flourish under great oaks. I was lucky to meet Salter when I had formed my own style and was too old for him to hurt me as a writer. I could still be influenced by him, and I was; for both of us, there was no more interesting subject than an adult male and an adult female in a room. If you read my book, you’ll see why I say “I split the difference between James Salter and James Patterson.”

The death of someone you know and admire affects you — affects me, anyway — in stages. Dealing with the news comes first; especially if you work in media, there’s often something you can or should do. Processing the death — getting your head out of the way so your emotions can slosh around — comes next. And then comes provisional understanding, the first stage of figuring out what it all means to you.

At Salter’s 90th birthday party, Nick Paumgarten reported in The New Yorker, “He looked fit and very happy in the white linen suit he only wore on special summer nights. He was sharp as a briar and very funny with his acknowledgment of all the speeches… He seemed hugely optimistic that night about a bit more time on earth.” A week later, he went to the gym, and died there.

I can be a bore about books I love, but I want to encourage you once again to read James Salter. Start with A Sport and a Pastime and/or Last Night, and if you’re hooked, go on to Light Years. About Salter’s memoir, Burning the Days, my brother said, “I stopped before the end, because if I finished it, I could never read it again for the first time.” Cute, but true. I envy all of you who will be reading Salter for the first time.

==============

When James Horowitz was 32 years old, he decided to end the life he knew — career Air Force pilot, buttoned-up husband and father — and become a writer. There was scant evidence he could succeed as a creator of stories and novels. But there was total certainty that he had to do it.

As James Salter, he invented a distinctive style, built on the integrity of the sentence. To Hemingway’s muscularity he added feminized insight; the result was prose that was as deeply emotional as it was taut and exact.

“She had a face now that was for the afterlife and those she would meet there.”

“She was a creature of blue, flawless days, the sun of their noons hot as the African coast, the chill of the nights immense and clear.”

“… glasses still with dark remnant on them, coffee stains, and plates with bits of hardened Brie.”

The sentences drop, regular as coins. The cadences are hypnotic. But Salter didn’t create that style to provoke admiration — his sentences are arrows to the real subject of his stories, which are, like the best stories about adult men and women, about honor and love in the face of death.

His breakthrough came in 1967, with the publication of A Sport and a Pastime, a short novel about the unlikely romance of a Yale dropout and a French shop girl in a small town. No one writes about France more lovingly than Salter; read a few paragraphs and you’ll want to buy a ticket. Not to Paris, though Salter gets its late nights and parties perfectly, but to the “real” France, where the smell of wood smoke is in the air and life is played out to the rhythm of seasonal change.

“Soon we are rushing along an alley of departure, the houses of the suburbs flashing by, ordinary streets, apartments, gardens, walls. The secret life of France, into which one cannot penetrate, the life of photographs albums, uncles, names of dogs that have died. And in ten minutes, Paris is gone. The horizon, dense with buildings, vanishes. Already I feel free.”

Cool prose, every word chosen, re-considered, affirmed. Mannered? Only until you get used to it. Then the world falls away and the book itself dissolves, and you are taken over by its characters.

Two reviews in The New York Times praised “A Sport and a Pastime” — Reynolds Price called it “as nearly perfect as any American fiction I know,” Webster Schott described it as “a tour de force in erotic realism.” But the eroticism was unsettling, the book thin, the publisher nervous. It became a “cult classic.”

Joe Fox, a legendary editor at Random House, was once asked which of the books he worked on would be called “great” long after their reviews were compost. There were two, he said. One was “In Cold Blood,” by Truman Capote. The other was James Salter’s novel, Light Years, for which Random paid Salter $7,500. That 1975 novel is considered his masterpiece. That is, now. At publication, a New York Times reviewer called the main characters “insulting to our patience and our expectations.” Another said the novel was “overwritten, chi-chi and rather silly.” Reviews like that do not boost sales. But readers who weren’t put off by characters named Viri and Nedra quickly formed the Cult of Salter, and word-of-mouth built an audience for Salter’s writing.

Fascinating short story collections followed: Dusk and Last Night. Isaac Babel famously said that “No iron can strike the heart with as much force as a period in exactly the right place.” That is why I’m particularly fond of the stories in “Last Night,” which strike me as a master class in fiction.

“He didn’t make much money, as it turned out. He wrote for a business weekly. She earned nearly that much selling houses. She had begun to put on a little weight. This was a few years after they were married. She was still beautiful — her face was — but she had adopted a more comfortable outline.”

Whew. That was fast. And efficient: “This was a few years after they were married.”

In these stories, privileged women pine for love — or sex. At a man’s funeral, there are women the widow has never seen before. A married man is having an affair with a male friend. A hill is made from a pile of junked cars. A romantic opportunity is missed.

There was a memoir at once lacerating and tender: Burning the Days. A delightful book about food with his wife, Kay Eldridge: Life Is Meals. His letters get published. And, in 2013, he was feted for his first novel in three decades, All That Is.

Salter had large hopes for this book. And it did make the Times list — for a week. But, as usual, his satisfactions were personal and private. “Redford phoned yesterday,” he wrote in an email. “He was in the south of France taking a break after all the business of the opening of his movie. He wanted to tell me how much he loved ‘All That Is.’ He went on for a while — I’m omitting the details out of modesty. He’d read it a second time, he said. He might even read it a third.”

Which is what you get when you are, as was so often said: “a writer’s writer.” Like this:

For the last three decades, Salter and I were friends. That meant small favors, dinners with our wives, and my unceasing efforts on my website to bring new readers to the cult. In 2013, he wrote me: “These days I am feeling how much I’d like to begin again, not from the very beginning but somewhere about a third of the way in.” Taking his “beginning” as his early 30s, that would put him in his 50s, his age when we met.

Because I always think of my friends as the age they were when we first encountered one another, I cannot think of James Salter as gone. Indeed, even when “All That Is” was described as a summing up, I preferred to write about this relatively thick novel as a prelude to the next book. And I see him now, eternally young, always looking ahead, surrounded by notebooks, turning words this way and that, struggling to write, not his final book, but his best one, aiming as ever for the only immortality worth having.

Salter had a cooler eye:

“Somewhere the ancient clerks, amid stacks of faint interest to them, are sorting literary reputations. The work goes on endlessly and without haste. There are names passed over and names revered, names of heroes and of those long thought to be, names of every sort and level of importance.”

For his readers, his name and work couldn’t be more important.