Books |

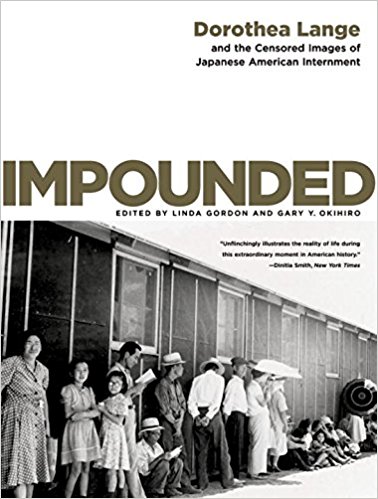

Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

edited by Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro

By

Published: Aug 17, 2017

Category:

Art and Photography

I tried hard to duck this one.

But my friend can be annoyingly persistent, and it was a book of photographs taken by Dorothea Lange, whose pictures of the 1930s define the Depression. It contained just a hundred pictures — and although they were of Japanese American internment camps in World War II, how terrible could they be? They weren’t concentration camps, were they?

“Impounded” arrived a few days before Charlottesville — my friend has an eerie sense of timing — and I read the essays and looked at the photos and put it down. I opened it again after Charlottesville and the astonishing VOX interview with the neo-Nazi, and those can’t-be-real press conferences, and I found a different book, the proverbial fire bell in the night: “Impounded” is a slice of our country’s dark history and a preview, if some people have their way, of our future. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.]

Context: Shortly after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt declared that all people of Japanese ancestry couldn’t live on our West Coast during the war. Between 110,000 and 120,000 Japanese residents, many of them American citizens, were relocated and incarcerated in camps. And there they remained, until the war ended. Were they a security risk? No. Did anyone stand up for them? Almost no one — even Dr. Seuss dashed off a racist anti-Japanese cartoon.

Dorothea Lange had documented the Depression for the Farm Security Administration. In 1939, she became the first woman to win a Guggenheim Fellowship. Her project was to document stable, insular rural communities: the Hutterites in South Dakota, the Amana society in Iowa, and the Mormons in Utah. But when the War Relocation Authority asked her to photograph the relocation of the Japanese, she set that project down and started her WRA assignment, working most days from 7:30 AM to 9:30 PM. And when she returned home in the evening, she often worked in her darkroom.

Lange had a platform built on the roof of her car so she could take pictures with a broader view. But a broader view wasn’t allowed. She couldn’t take pictures of barbed wire, armed guards, or watchtowers. Security staff followed her. For a photographer whose style was intimate portraiture, doing her job was an ongoing challenge.

Still, she took 700 pictures she could print. The government owned them, and the government wanted to relegate this chapter of our history to the dustbin, so no one saw them. Literally. On a few, an administrator scrawled IMPOUNDED. And they remained unseen until 2006, when this book appeared.

The book begins with two eye-opening essays, and then there are four chapters of photographs. Before the evacuation. The roundup. At the assembly centers. Manazanar (one of the camps). Ansel Adams also visited the camps and took very different pictures. His show people making do. Hers show people being done to.

There are slideshows online, hereand here.

There are currently two exhibits of these photos. Chicago. And the Roosevelt Library in Hyde Park, New York.

They’re also for sale.

Question: Are these concentration camps?