Books |

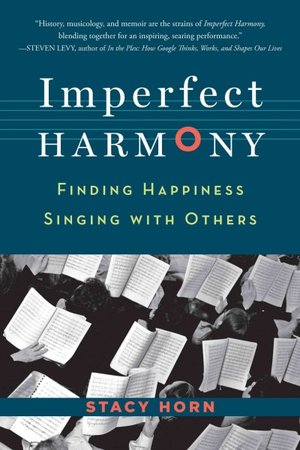

Imperfect Harmony: Finding Happiness Singing with Others

Stacy Horn

By

Published: Sep 24, 2013

Category:

Non Fiction

Thich Nhat Hanh gave a lecture in Boston, but he wanted to do more, so his staff arranged a free “Sit in Peace” event in Copley Square, a few hundred yards from the site of the Marathon bombing. It wasn’t like any event I can think of — on a sunny Saturday afternoon, he came out, sat down and said nothing. For 25 minutes. A crowd of 2,000 people shared the silence with him. The Boston Globe: “He made the city center quiet along with him, to the point where any noise — a skateboard, a car horn, a passing duck boat tour — seemed out of place.”

“Peace and quiet.” That’s not a cliché. Neither is its opposite: people coming together, often in a sacred space, to sing in harmony. Does it grate that they sing to praise a god that’s not mine? Not at all. Only the group effort matters. And the merging of many voices.

From time to time I commend choral music to you. The Faure Requiem. Allegri’s Easter classic, the Miserere. Anything sung by the Tallis Scholars. The Vivaldi Gloria and other sacred music from Vivaldi.

I come to this music as a listener. Until recently, I was clueless how it feels to sing in a choir. Then I read “Imperfect Harmony: Finding Happiness Singing with Others.” The author is Stacy Horn, who I remember from the early days of the Internet as the founder of Echo, a New York chat salon a decade ahead of its time. That’s a cool achievement, but it doesn’t really describe her. As she coolly assesses her life, “Boyfriends come and go, jobs come and go, cats live and die, a stay in rehab when I was thirty, broken engagements and the deaths of those I love.” The one constant? Singing. For 30 years, she’s been a member of the Choral Society of Grace Church.

“Imperfect Harmony” is the record of her experience, and because she’s Stacy Horn, an inveterate researcher, you get a lot in 264 pages. Romances, mostly failed, and the hope of finding a new one when new people join the choir. Rehearsals, so well described you feel as if you’re in the room. Reader-friendly accounts of some of the pieces the choir sings. Sharp anecdotes: In a concentration camp, a choir of Jews sang the Verdi Requiem, even though they had to replace their members four times in a single year. It’s a dazzling book, never hitting a false note and, quite possibly, inspiring you to think about joining a choir. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Should you be motivated to raise your voice with others, know that’s not a minority impulse. As Horn writes, “32.5 million adults sing in choirs, up by almost 10 million over the past six years. Many people think of church music when you bring up group singing, but there are over 270,000 choruses across the country.” That includes the show choir your kid is in. And, of course, “Glee.”

Most of those singers would not make it past the first round on a reality show. That, says Horn, is not the point. Music creates relationships. It affects your brain chemistry — it’s “the perfect drug.” And it provides great comfort: “I’m one day poorer and another day singler and we’re all going to die, but together with all these people I have raised my voice.”

“I am not a great singer,” she tells us, but listen to how the book ends: “We sang that section over and over, reveling in the warm glow of our voices and the magic current of potential that comes to life whenever people are drawn together by the astonishing and irresistible power of a song.”

I closed the book and felt at peace.

BONUS VIDEO

Horn’s choir sang a modern masterpiece, “O Magnum Mysterium,” by Morten Lauridsen.