Books |

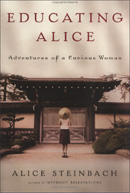

Educating Alice: Adventures of a Curious Woman

Alice Steinbach

By

Published: Jan 01, 2005

Category:

Travel

The dollar shows no signs of getting off its sickbed. That means a cafe creme can cost $7 in Paris. In London, the subway will set you back $4.

I see a lot of armchair travel in our future.

Funny travel books — like A Walk in the Woods, Bill Bryson’s chronicle of the Appalachian Trail — will do it for some. Ditto Schlepping Through the Alps, Sam Apple’s sociology-drenched look at sheep herding in Austria. And you can get a vivid sense of a country and its people (in this case, Norway) in a tense historical account like We Die Alone.

But I think a great many armchair travelers — women, especially — will identify most intensely with someone they feel is a sister. Say, a woman over 50. Divorced and not looking to remarry. Interested in life, and eager to dive deeper into the things she loves — French cooking, gardening, Jane Austen, and more.

Alice Steinbach is not quite that woman. For one thing, she’s not the divorcee-next-door — she’s won a Pulitzer Prize. For another, she has a cultured Japanese lover who has a way of showing up in the European cities she visits. And then there’s the matter of money; unless she worked out some deals or scored a humongous book contract, some of her adventures add up to a pretty penny.

You forgive Alice Steinbach her advantages because she does one very difficult thing impossibly well — she travels alone. It’s just Alice and her notebooks. And her willingness to engage, which is considerable; this is an enthusiast who throws herself into things and wants contact with her fellow adventurers.

In "Cookin’ at the Ritz," therefore, she learns a lot more than a few kitchen tricks in her class at the legendary Paris hotel. She goes to school as well on the chef. And her fellow students. She’s brought up short by the distance between expectation and reality — at the end of the day, she’s beat, and as for the food, "after tasting and smelling food for more than three hours, my appetite always lost its edge." (In case you do get to Paris, she offers some astute recommendations: the great tea salon Laduree, Dallyou’s dessert shop, the market on rue Montorgeuil.) But she doesn’t miss the deep pleasures ("I let the dark chocolate melt in my mouth and then slide slowly down my throat") and the Big Picture ("The act of cooking forced you to live in the present tense"). And there’s a touching coda. In the gift shop, she impulsively bought a white paper toque. She would not dream of wearing it: "To me, it would be like playing Yo-Yo Ma’s cello while he was out of the room."

I like cooking and Paris, so I was hooked by that first chapter. I was almost equally intrigued by Alice’s time in Kyoto, where she befriends — and is befriended by — the women who are her guides. They force her to look more deeply into her own life. "I think that even when we travel alone we bring a companion: our past," she notes. And bows deeply to those who led her to this perception.

Florence is a different flavor. She goes looking for one thing and finds another — it’s a Nancy Drew mystery story that starts with a bonsai garden and ends with the terrible floods of 1966. Her reportorial skills sustain her; you see, and admire, her method of learning more about the most seemingly random subject. She’s on less firm ground in Winchester, England, where she attends a convention of Jane Austen devotees who, clearly, know more than she ever will. Nonetheless, she’s a good sport, open to the experience, and so she makes some lovely friends-in-Jane.

I like going, and I like coming home; about halfway through, I realized that home is not in the cards here, and the incessant travel began to wear me down. Like a churlish traveler who’s seen too many hotels and taken too many planes, I found myself dutifully slogging through Cuba. Gardens bore me; I skipped the chapter on Provence. I’m allergic to writing classes; I recoiled from the one Alice joined in Prague. And her stint learning how to be a shepherd in Scotland left this city boy cold.

Then again, there’s nothing more subjective than travel; my delights could be your despair. The point, as the ads for the cruise line trumpet, is to "get out there." Alice Steinbach does — fearlessly, honestly and triumphantly. I’d take an armchair trip with her almost anywhere.