Books |

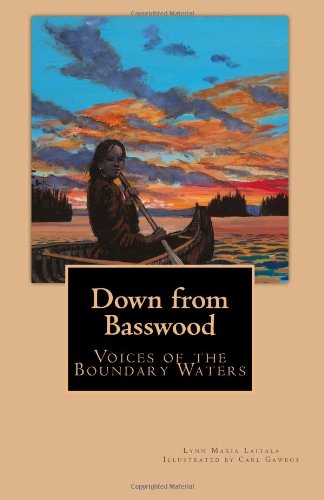

Down from Basswood: Voices of the Boundary Waters

Lynn Maria Laitala

By

Published: Oct 18, 2015

Category:

Memoir

In the decade I’ve been publishing this site, I’ve never run a piece about a book that carried the byline of the author. And I’ve never published a piece with a real estate advertisement attached. But the person best suited to write about the North Woods of Minnesota is the woman who wrote the best book about it. (How do I know? My family and I have been spending the week of July 4th in Ely for more years than I’ve been publishing this site.) And as for the real estate ad at the bottom of this piece, it just seemed that someone who read about the area and formed a picture of it as a magic place might want to dream. So much for “never.” Here is Lynn Maria Laitala.

Once I asked my father-in-law what Chippewa heaven was like.

“Here,” he said. “Just like here.”

“Heaven can get to 40 below?” I asked. “Heaven has black flies and mosquitoes?”

“Yes,” he said. “This is heaven. There is nothing better.”

My father-in-law was an Indian, born at the turn of the twentieth century on a lake straddling the border between Minnesota and Ontario. He spoke only Chippewa until he was 19. Then his father sent him to boarding school in Wisconsin to learn English and read the Greek and Roman classics. He returned home and married the teacher the county sent to teach at the reservation school. (This was far from unprecedented — Chippewas had been marrying Europeans for two hundred and fifty years, first the French and then the British in the border lakes between Minnesota and Ontario, now known as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.)

During the fur trade, the border lakes were a great highway. Then American corporations arrived in the 1880s to mine iron ore and log the forests, a devastating change for the land and the old communities it supported. Still, the traditional culture of cooperation continued in the mining towns and logging camps. Indians taught woods culture to immigrant miners and loggers, and those workers hunted, fished and harvested wild rice to keep their families alive during layoffs, strikes, depressions and shutdowns. European peasants from thirty-five different countries found that they shared fundamental values with each other and with natives. Cooperate with each other. Take only what you need, share what you have and don’t waste: the land will provide.

My father and mother-in-law eventually moved back to her family homestead near Ely, Minnesota. They raised eight children; all went to college.

When my husband was a young man, his father took him on a canoe trip between Lake Vermilion and Rainy Lake, a route well traveled during his youth. As they launched their canoe in each new lake on the journey, the father sprinkled a little tobacco as a gesture of gratitude to the manitous. Manitou has been translated as god or spirit but a better translation is “mystery.” Offering tobacco acknowledged respect for the mysteries of creation and for the life it sustains.

I was born in a boardinghouse in Winton, the end of the road at the edge of the wilderness. Imagine a village of old men, sitting on benches in the sunshine, talking quietly in Finnish. There were children in the village and an equal number of dogs, but even added together it seemed that we were outnumbered by the old men.

Winton was founded by great Weyerhaeuser interests that cut down the forest home of the Chippewas on Basswood and the other lakes in what is now in the BWCAW. By 1921 the profitable timber was gone and the lumber mills shut down. Only a few families stayed on, along with most of the single men who were brought to work in mills and woods as young men and had never found wives. They made their living by hunting, trapping and fishing.

In 1928, Sigurd Olson bought the Border Lakes Outfitting Company and began to promote the tourist industry. My widowed grandmother supplemented her income by sewing the sacks Olson used to pack flour, sugar and other supplies. In addition to running the boardinghouse and sewing sacks for Sigurd Olson, Grandma took in laundry and worked as a practical nurse, leaving her own four children at home to attend the sick. She told her three daughters that they had to get an education. A man could always find work. but a woman had to have an education to get good pay. The girls took her advice. Two got master’s degrees at a time when it was rare for women to get a higher education. Then, after they had lived and traveled throughout the United States, both returned to Winton. They had found nothing better.

The old trappers and guides wintered in the boardinghouses in Winton, but many spent the warmer months in their cabins on Fall Lake, beautiful log buildings with dovetailed corners, set back so they didn’t mar the beauty of the shoreline. Each cabin had a table at the window, a bench along the wall, a small cupboard, a narrow bed, and a wood cook stove. The simplicity, order and quiet were deeply reassuring.

Those men had come to America because they had been promised that they could earn money to buy land, marry and raise families. None of it had happened. They were paid poorly and treated badly in industrial work before the mills shut down and they were abandoned.

As a child I didn’t know about the hardships the old bachelors had known and the destruction of their youthful dreams. They so relished telling stories of their adventures in the north that I couldn’t imagine there was any other life the old bachelors would have rather lived.

When I was a child, younger men with families commuted to work in the iron ore mines in nearby Ely. After the mines shut down in 1967, some of the miners traveled to work in the taconite plant in Babbitt some twenty miles away. Most of their children had to leave to find work.

In the mid 1970s, I met my husband on the Fernberg Road 15 miles beyond Winton. We had both come home after living as far away as Oregon and Montana. Not long after we married, the Boundary Waters became a hot spot in a national battle over legislation that expanded legal wilderness designation. In Minnesota it ripped apart north and south, devastating Minnesota’s Democratic Party. In the north it was seen as a war between ethics and law, between community and wilderness — special land where people travel and do not remain.

I was afraid that the history of the place would be lost in the rhetoric of the conflict. I believed that the secret of the remarkable power of that land to heal the spirit lay in the stories of survival in a hostile environment, in the triumph of hope over despair.

My husband Carl Gawboy and I were united by love of our place. But we moved away, and after two decades we parted. In the grief of that ending I began to write “Down from Basswood” to remember the spirit of the place. Carl illustrated the stories. They are about people who understood what heaven is like.

[To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

—

THE HOUSE ON LOST GIRL ISLAND

This family-built cabin is located on 975’ of lake shore and 9+ acres on Burntside Lake, one of Minnesota’s premier lakes. It offers absolute privacy and unique Latvian style, with hardware on the doors and the deep eaves reminiscent of old Latvian farm buildings. And here — how totally today is this — is the drone tour.