Books |

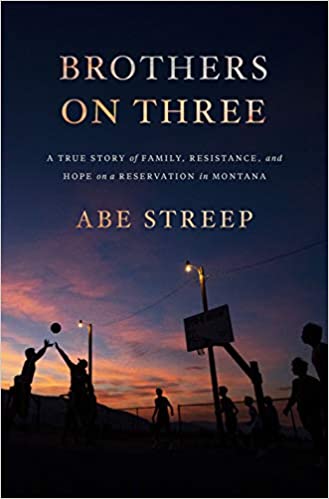

Brothers on Three: A True Story of Family, Resistance, and Hope on a Reservation in Montana

Abe Streep

By

Published: Sep 12, 2021

Category:

Non Fiction

If I can’t identify the players, I can’t watch the game. So… no football. If I can read a book in the time it takes to watch a complete game, count me out. So… no baseball. But basketball? Five easily identifiable players, a big ball, a shot-clock… I’m there. More, I like to read about it. John McPhee’s gorgeous book about Bill Bradley at Princeton. LeBron’s book about his high school years. And, when I remember I wrote it, my book for kids about Michael Jordan.

Ah, Jordan. The greatest. He knew it, and Chicago knew it, and you were reminded of it even before the game began. The lights dimmed. In darkness, music began… percussive, bass-heavy, throbbing music. And then the players were introduced, one by one, Jordan last. Watch it… and crank the volume. If you were there, you know: the crowd blew the ceiling off the roof. Watching on TV, I screamed.

Now picture Phillip Malatare and Will Mesteth, the stars of the Arlee Warriors, coming onto the court. The scale is different — there are 602 residents of Arlee, Montana, and this is a high school game — but the emotion is about the same. On the reservation, where joy is in short supply, these kids are rock stars. And in a state that leads the country in suicide — between November 2016 and November 2017, there were 20 deaths by suicide on the reservation — they carry the hopes of their community. “Do not forget,” their coach tells them before the game, “you’re doing this for every kid in the world that’s ever looked up to a basketball player coming off the rez.”

A few years ago, Abe Steep, a journalist “from a New York suburb rife with contradiction,” went to the Flathead Indian Reservation to write about the Arlee Warriors for The New York Times Magazine. [Disclosure: His parents and I are close friends. I’ve met Abe Streep once.] Now, in 307 pages, with 30 pages of notes, there’s a book.

“Brothers on Three” is, as the subtitle suggests, more than an account of a championship season. “Family, Resistance, and Hope” are serious themes in any community. They resonate more deeply in a community of people who have been exploited for centuries, where the median income is $22,000, and whose high school basketball stars have one hope of getting out of town: an invitation to play college ball.

That invitation is more elusive than the golden ticket in “Willy Wonka.” Will and Phil can surely go to a community college. They deserve better — to play for the University of Montana. But the university only retained 51.6% of its Native American freshmen in 2017. And its team plays a different style of basketball. So they wait for a call that may never come.

The players have family, often extended, and the history of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes is central to the team’s identity — the cast is large and, for me, kaleidoscope. You may be similarly overwhelmed. Press on. The closer the season comes to the playoffs, the more the drama ratchets up. Will ignores blood in his urine — a kidney stone, it needs to be removed — so he can keep playing. A bucket near the bench for vomiting. Two-man fast breaks in which the ball doesn’t touch the floor. And, looming like Darth Vader, the rivals: Manhattan Christian, a faith-based private school near Bozeman. [To read an excerpt, click here. For the New York Times review, click here. To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

And the suicides! On the eve of the tournament, another one! The players make a video, expressing their sadness and urging anyone who feels terminally sad to seek help. The video goes viral. Cue the Nike executives, who show up with shoes and an invitation to visit Beaverton. Zanen Pitts, the Arlee coach, sees a mission and is, understandably, blinded by the light. The school superintendent gets involved. The players start to seem like minor characters.

In fact, the players are heroic. The pressure on them is crushing and unending, and they rise to it, again and again. The last half of the book was a blur for me, I was so eager to learn if the Warriors would get the storybook ending they deserved. Caveat: storybook endings aren’t what they used to be. On the reservation, they never were.

At one point, Streep correctly wonders about “a white man writing about life on a Native American reservation… another white guy in Indian country.” Good question. On the evidence of “Brothers on Three,” they were lucky to have this one.