Books |

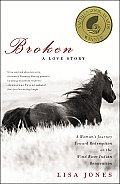

Broken: A Love Story

Lisa Jones

By

Published: Sep 29, 2010

Category:

Biography

It’s two for one in "Broken: A Love Story" — biography and autobiography merge in the dusty horse corrals of Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation. Take one student, give her one teacher. And as the Scottish-American journalist investigates the wisdom path of Stanford Addison, you know you’re going to get more than a good story about this Arapaho’s uncanny skill as a horse gentler.

In “Broken: A Love Story,” we are led into the “post-apocalyptic” world of reservation life in central Wyoming. The value of entering a world so cut-off from mainstream America — more: so assiduously ignored by it — is immense. Jones passes back and forth across that reservation boundary line for four years, investigating and absorbing Stanford’s life, until for her the line vanishes. (To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.)

What can be learned from a broken culture? Stanford’s horse gentling techniques speak for themselves. A tether he’s designed, hooked to a line above the corral, means the only place a wild horse can stand squarely on four feet is directly below the hook. New horses fight and fume and stew until they see “the only way to endure confinement is to accept it.” Stanford calls this “finding your center.” He tells horses he cannot save them. He lets them learn to save themselves if they will.

Jones’ willingness to move closer to Stanford and his extended tribe comes largely from her respect for how they find that center, amidst great suffering. She witnesses early deaths, diseases, abandonment, boredom, unemployment, hunger, a botched horse castration. And she learns, she says, that life breaks all of us, whether we admit it or not.

But to be broken is not to be defeated. If you do it right, it’s to surrender to the whole mess, to the wild extremes of aching beauty and joy as well as terrible hardship and loss, to accept winter as well as spring, and summer, and fall. Stanford Addison shows her that surrendering to life is an authentic gateway to freedom.

The strange truth is, acceptance of suffering can lighten the load. Jones writes with characteristic humor and honesty: “I thought I was in heaven the way a goose flying on the fine salt breezes near La Guardia Airport thinks it’s in heaven right before it flies into the landing route of a 747 from Kansas City.” A journalist friend warned her that she was getting too close to her sources. She ignored that well-meaning advice:

….engines of unfathomable joy had chugged to life. I got rushes of ecstasy from Stan, the only person I’d ever known who constituted a conduit to the divine. Then there was the happiness that comes from living in a tribe. I’d never felt it in my life, but I knew what I liked. Plus, it was dawning on me that I, too, had been native before, although I’d forgotten all about it. I once lived on a rocky outcrop in the North Sea where people who looked like me had made their homes for thousands and thousands of years… I had been homesick, not to mention heartsick and Godsick, for thirty years… I wanted to know people who had a sense of home, and if they didn’t have it, at least knew it was missing.

Jones’ memoir is rich with unexpected homecoming. And with love that is not personal. “Negative capability” — the phrase Keats used to describe accepting discordant realities — moves the hearts of both Stanford Addison and Lisa Jones. In “Broken,” unimpeded by resistance, the negative becomes the positive. And back again.

— Jeff Fuller is a writer and designer who lives in Boulder, Colorado. Barbara Richardson is the author of a debut novel Guest House.