Books |

Bob Dylan: The Philosophy of Modern Song

By

Published: Feb 14, 2023

Category:

Entertainment

GUEST BUTLER CHARLES WARNER is a retired college professor, author, and blogger at MediaCurmudgeon.com. He is the Goldenson Chair Emeritus at the University of Missouri School of Journalism and taught for 25 years as a part-time Assistant Professor in the Media Management Program at The New School in New York. The fifth edition of his textbook, Media Selling: Digital, Television, Print, Audio and, Cross-Platform, published in July, 2020, is the most widely used sales textbook in the field and has been adopted by more than 70 universities worldwide. Until he retired in 2002, he was Vice President of AOL’s Interactive Marketing division.

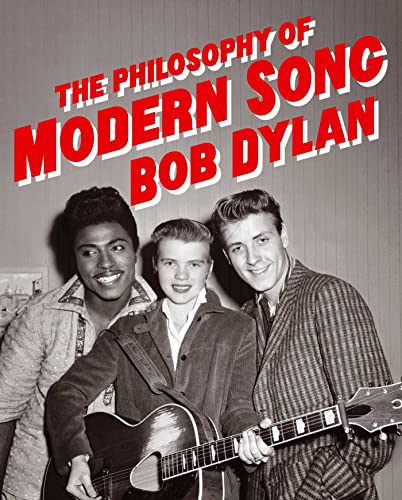

Bob Dylan’s new book, “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” is a banquet of creativity and surprises. In 66 short essays, he discusses songs he loves and the artists — only four of them female — who recorded those songs. It’s a thick book: 350 beautifully illustrated pages, with shots of old American record shops, casinos, fairgrounds, and movie theatres.

In case you’re among those who wonder how Dylan won the 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature, wonder no longer. Dylan’s not an entertainer in any traditional sense of that term. At this point in his life — hard to believe, but he’s now 81 — he writes to please and amuse himself. His writing is magical, bewitching, beguiling, wacky, penetrating, deeply knowledgeable, and surprising. [To buy the book from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

Samples…

“Key to the Highway” sung by Little Walter, begins:

“It’s ironic, a lot of dignitaries give you the key to the city. That indicates that everything in the city is open to you for inspection at any time. I have gotten lots of keys to different cities, but I’ve never really tried to inspect anything yet.”

His take on “My Generation,” by The Who, begins:

“This is a song that does no favors for anyone, and casts doubt on everything. In this song, people are trying to slap you around, slap you in the face, vilify you. They’re rude and they slam you down, take cheap shots. They don’t like you because you pull out all the stops and go for broke. You put your heart and soul into everything and shoot the works, because you got energy and strength and purpose. Because you’re so inspired, they put the whammy on, they’re allergic to you, and they have hard feelings. Just your very presence repels them.”

On Elvis Costello:

“When you are writing songs with Burt Bacharach, you obviously don’t give a fuck what people think.”

His one paragraph on “Long Tall Sally,” by Little Richard, compares Sally to the giants of the Old Testament; he sees Little Richard as “a giant of a different kind,” who took a diminutive stage name “so as not to scare anybody.” Only Johnny Cash, Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart are mentioned twice. You’d expect his idol Cash to appear more than once, but Rogers and Hart? Surprising.

But maybe not, if you look at his choices as aspirational. Here’s a short, uncharismatic, unsexy, unhip, poor, Jewish kid from a small town in Minnesota who moved to New York when he was 20 and who identifies with the struggles, poverty, and loneliness of someone young living in a big city. As he writes in Chapter 1: “Your life is unraveling. You came to the big city and found out things about yourself you didn’t want to know, you’ve been on the dark side too long.”

So Dylan aspires to be as big, handsome, and macho as Johnny Cash. As sexy, charismatic, and animated as Elvis. As energetic, magnetic, and wild as Little Richard. As warm, smooth, and lovable as Willy Nelson. As hip, finger-popping, and confident on stage as Bobby Darin.

But we know he’s none of these, and so does he. He’s not a Boomer — he spent winter nights in the ‘50s listening to distant radio stations. When he made it to New York and started writing songs, some reflected the real world, more reflected his. The major takeaway from “The Philosophy of Modern Song” is that the world’s greatest living songwriter believes a song is good if it makes you feel sad, happy, sexy, wistful, angry — anything as long as you feel alive.

Does he care if you like the book? Not at all. Does he read reviews? No way. I call that refreshing.