Books |

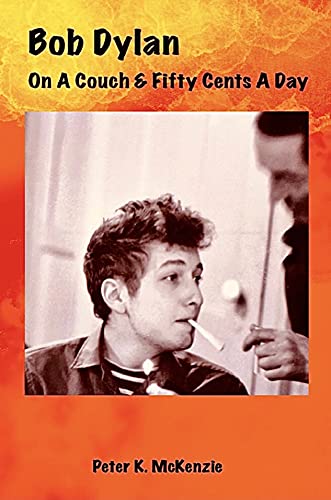

Bob Dylan On A Couch & Fifty Cents A Day

Peter McKenzie

By

Published: May 23, 2021

Category:

Biography

“Eve and Mac McKenzie took me in an’ they were beautiful… I lived with them…and they fed me…and I stayed out all hours an’ came back in and went to sleep on the couch. An’ Peter was there. I was his idol…now he’s 18, 19. He’s in college. He’s a very smart kid…they know me well. Talk to them.”

– Bob Dylan, 1965

May 24, 2021. Bob Dylan turns 80. A million years ago, Pete Seeger was among the first to ask him where his songs came from: “Do you just spread out the newspaper in the morning until you find the story that really gets you upset?” Dylan: “I really just take them out of the air.”

True. And like all magicians, he didn’t invite spectators to watch him do it — except in 1961. He was 19, just becoming “Bob Dylan,” and in mid-May, when he showed up at the New York apartment of Eve and Mac McKenzie, he had nothing… and nothing to hide. He was supposed to stay one night. By the time he left in mid-September, he had become a hero and big brother to their son Peter, a 15-year-old high school sophomore.

All these years later, Peter McKenzie remembers everything: interactions, conversations, descriptions of early writing attempts, never-seen-before images of handwritten song drafts, accounts of guitar and harmonica lessons. And “Bob Dylan On a Couch & Fifty Cents a Day” doesn’t end in 1961 — the McKenzies became Dylan’s surrogate parents, and he visited them many times over the decades for their advice and encouragement

For three generations, people have been trying to figure out how Bob Zimmerman became Bob Dylan. There have been books by the dozen. What occurred during his stay with the McKenzies — people he trusted, loved, and learned from — is the unknown, missing piece. This book is an all access pass to a magical time. [To buy the Kindle edition from Amazon, click here. To buy the paperback, click here.]

Some samples:

Bob always looked out for me. If I liked a shirt he was wearing he let me wear it. On many afternoons when he finished his daytime business he’d take out his guitar and the lessons began. He showed me his music techniques as well as the special way he played harmonica.

“Brownie McGee played this way,” he would say. “Jesse Fuller played this way. Now master them and you’ll come up with your own style.”

No one else got that kind of tutelage from him. If I had a problem with any of my contemporaries, he’d advise me how to handle it. He loved my artwork and always asked me how I got my ideas. We talked about history and literature. I met his fellow musicians when they dropped by the apartment, or when we’d go on outside adventures together.

It was always the real Bob; no pretense of hiding behind a mask, unlike the many other personas he began trying on for public consumption as time and fame progressed.

Patiently, he even gave me pointers about my homework, particularly my essays. Truth be told, in private, Bob had a perfect command of the English language; his grammar was impeccable. On stage it was purposely another story.

My mother and Bob developed a regular morning routine. He would get out of bed, usually around noon, tousle his hair, put on a pair of pants and a shirt. He accumulated a few more items of clothing, some coming from Dad’s closet, which Mom offered him. He didn’t have to ask. He would walk to the bathroom, wash his hands and face, and (contrary to legend) brush his teeth, go into the kitchen and light a cigarette as he sat down at the table for breakfast. My mother usually made him eggs, toast and coffee, but he never went to the refrigerator on his own even though he was treated as a member of the family with all family privileges. He was the perfect houseguest, gracious and well mannered.

Over breakfast, he and Mom would talk about the previous night’s events — what he did, who he’d met, the kind of friends he was making. That morning ritual was probably the most relaxing part of Bob’s day.

He dropped by late one afternoon a couple of years later, in mid-1963, right before I left for college. After saying goodbye, my mother called out to him.

“Bobby, I’m concerned. I know from being in show business with musicians and actors that things like marijuana and other items eventually show up. You have to be careful.”

He stopped on a dime, turned around, and in his calmest, most serious voice said, “Eve, you know me. I would never get into that.”

“You promise?,” she said.

“Aw, c’mon. Why would I?” He looked up and smiled reassuringly.

In the late afternoon, one early June day, I came back from school after a detour to the grocery store. My mother and Bob were in the kitchen talking. I could see he was sitting forward in the rocking chair with his guitar in his hands. This time the sound coming out of it was unlike anything I was familiar with. When I walked into the kitchen I saw, covering his left pinky finger, something that looked like the top of my mother’s lipstick holder. In fact, it was the top of my mother’s lipstick holder.

Earlier Bob had asked: “Eve, do you have any lipstick in the house?”

“What, you have a new girlfriend you haven’t told us about yet?”

“Nah. I need the top of the lipstick case to put on my finger so I can get a certain sound out of the guitar. I found out about it from an old, black blues player while I was passing through the South.”

Mom smiled at him: “For you, of course. Let me go get it.”

As she smiled she was thinking: “That young man has as likely been down South learning guitar tricks from an old, black blues guitar player as the moon is made of cheese.”

She kept the thought to herself and came back into the kitchen with the top of the lipstick container and gave it to him.

“Is this what you are looking for?”

“Yep, Eve. It’s just right.”

“So Bobby, what did your blues man friend teach you?”

She smiled at him, again.

He started to show her.

In July 1961 Bob came and went, making new friends, sometimes bringing them up to the apartment to see how my folks would react.

One evening a group of people, mostly friends of my parents, gathered at the apartment. It was a nice social get together. Bob was there. In the midst of the chatter the subject turned to Bob. They all knew him in one form or another and liked him. But then some started giving their unsolicited advice on his appearance and his wardrobe. They weren’t putting him down — just trying to be helpful because they thought they knew better.

“Kid, you’ve got a lot of talent, but you dress like a vagabond with your wrinkled clothes and your hair messy. If you want to make the right impression you should put on a jacket and tie like some of those other clean-cut looking kids and comb your hair. People will take you more seriously. You’re a nice looking young man and you should dress appropriately,” one said.

I was surprised by the ferocity of my mother’s immediate response. The firmness with which she spoke gained everyone’s attention.

“I know you mean well on Bobby’s behalf, you have no real idea how show business works. His clothes are always clean. That’s always made sure of. If they’re wrinkled it’s on purpose. It’s his choice. I could iron the clothes anytime he wants, but he doesn’t want that. If his clothes seem mismatched it’s not because he has no taste. It’s done on purpose. He is very conscious of the image he presents. That’s why he does it. He has a plan. He’s his own man and I, for one, agree with it. He is doing just fine, thank you. He knows exactly what you’re saying and has made a conscious decision not to dress up like men in suits. It’s the absolutely wrong time for him to dress like a prep school boy. And don’t even think about making a comment on his cap. One day, though, I predict, you will see him not only wearing a suit, but a tuxedo. Just not now.”

That put a clamp on any further comments, or discussion of Bob’s wardrobe and hairstyle. He remained silent the entire time, not involving himself in the matter. When everyone finally left Bob turned to her.

“Thank you, Eve.”

She stopped what she was doing, went over to him, gave him a kiss on the cheek.

“You’re doing fine just the way you are.”

“You know, you know when I knew I had arrived? When Albert (Grossman) said to me, ‘Which actress or model do you want to go out with. I’ll just make a call and it’s done.’”

“Some things in this world never change,” my father replied, with a knowing smile.

In the Fall of 1962, at the beginning of high school senior year at the High School of Music and Art, I was elected as an officer of the student body on a campaign promise to bring folksingers to perform at the school.

“Bobby, I just got elected to the student body,” I told him.

“Congratulations, Pete.”

“Thing is, I promised to bring folk singers to perform for the school. Would you do it?”

“Sure. Just tell me when. If there’s no scheduling conflict I’ll be there.”

I went to the faculty adviser for approval. I figured it was just a formality. She asked only one question.

“Does he wear a tie?”

“He normally doesn’t,” I answered truthfully.

“That’s unfortunate. Since he doesn’t wear a tie he can’t perform for us,” she curtly replied.

There are 65,000 words in this book. Stories told nowhere else. Photographs you’ve never seen. The very definition of “essential.”