Books |

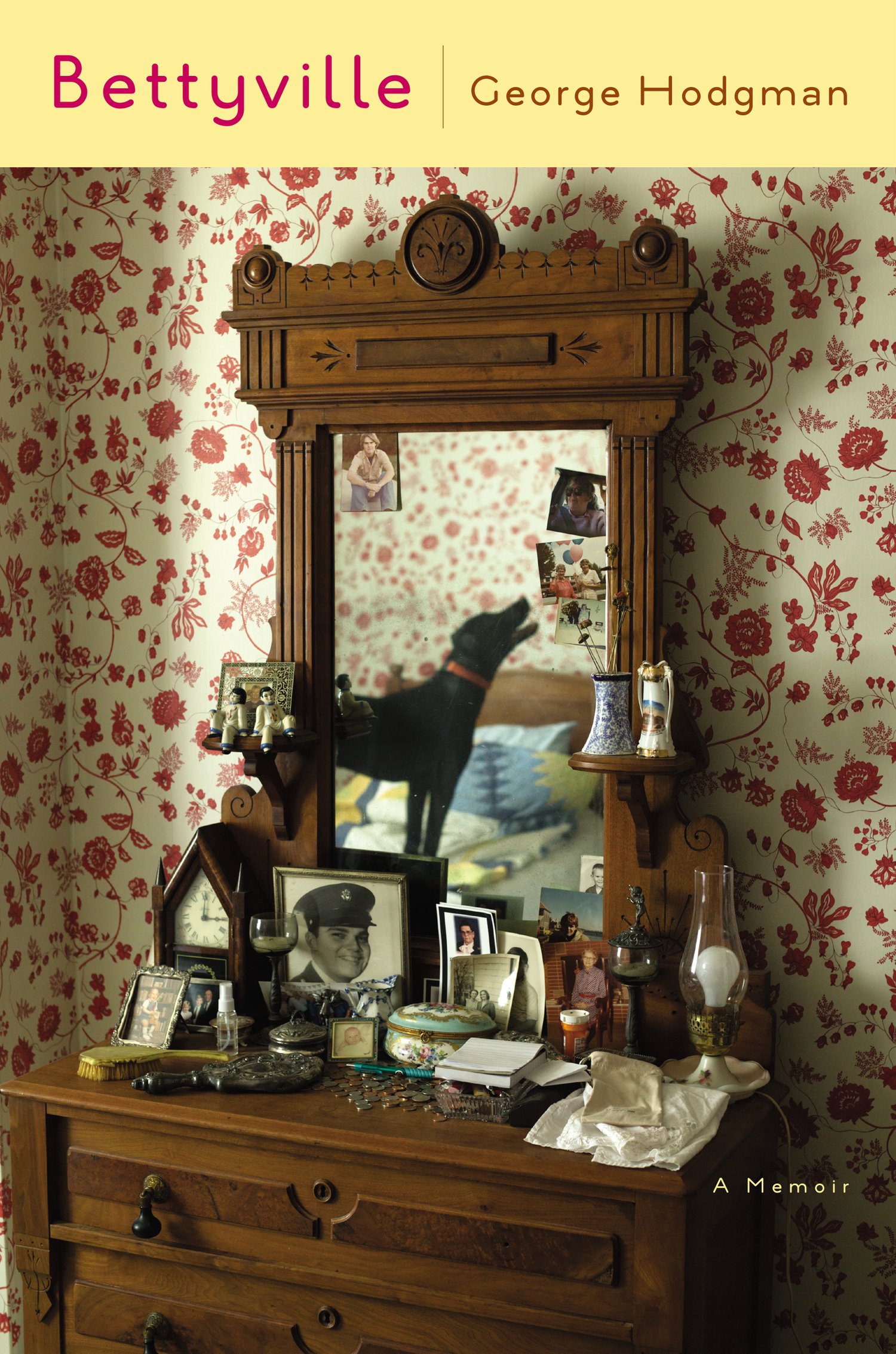

Bettyville

George Hodgman

By

Published: Mar 08, 2015

Category:

Memoir

George Hodgman died on July 20, 2019.

When George Hodgman was a boy, he and his mother ended the day holding hands and praying. Not just for themselves, but for all the people in their tiny Missouri town. “We made our way from one street to the next, we asked for help for those suffering in this place or that, for people who were poor or who had lost someone, or those who had found themselves in trouble.”

George asked his mother if these prayers worked.

“It is something we can do for one another,” Betty Hodgman said. “We have to understand we are all together here. We have to try and help people.”

Betty had some eye surgery. She feared she was going blind. George wanted to pray for her, but he was embarrassed to do it in her presence. So he asked if, that night, he could say his prayers on his own.

“Her face changed,” he writes. “She dropped my glasses on the table and looked down at her lap before pulling away. I wanted to take it back, but it was too late, she was gone. She left so fast. She didn’t bring it up, but the next night she did not come to my room. Never again would we have our special time. She would not risk being sent away again. I grew up to be just like her. Like my mother, I flee at the slightest suggestion I am unwanted.”

This anecdote says so much, and a lesser writer might have started the book with it. George Hodgman buries it on page 164. Why hold it back? Because, at the surface level, “Bettyville” is a simple story: a charming but difficult man comes home to care for his charming but difficult mother. Betty, in her 90s, is winding down, suffering from dementia “or maybe worse.” George was once a valued editor at Vanity Fair — where, in my day, the office politics were so Mandarin that putting out the magazine was almost an afterthought — and at a publisher. He got downsized; now he’s a freelance book editor in Manhattan. But his father’s dead, and he’s an only child. Off he goes to Paris, Missouri (population: 1,220).

That’s one story, and it’s often an amusing one. First, because Betty is a crisp tennis partner for banter, George’s best game. “You’re a mean old woman. You’re not a bit good,” he tells her. And she shoots right back: “I can’t believe you’re not in the penitentiary.” And then there’s the odd couple angle: “A month ago I thought the Medicare doughnut hole was a breakfast special for seniors. I am a care inflictor.”

A close second to George-and-Betty is the story of George, the proverbial hot mess. He’s gay, but perennially unattached: “My life has been an odd hotel with strangers drifting through.” Complicated? “I am a loner, but I hate to lose people.” His virtues — he’s a hard worker, he must always get it right — may not really be virtues: “I have spent my life trailed by voices in my head saying, This isn’t right. You’re not right.” And not because he’s gay. It’s that his sexuality has baffled and disappointed his parents so completely that they could never talk about it.

Inevitably, George becomes “a performer, an artist skilled at distraction, control: ‘Look at me, but don’t see. Watch, but not too closely.’” And he’s very good at it. His problem isn’t gay marriage, it’s “gay dating.” At rehab, he’s asked if he has trouble with intimacy. “Only when I try to get close to someone.” In his lexicon, he’s not emotionally unavailable, just “temporarily out of stock.” The only cuisine he’s ever mastered: “seasonal drugs.” He won’t ask Betty about her funeral preferences because he’s “fearful that she will demand a salad bar.” I leave it to you to insert the drum rolls.

These threads are expertly woven together, and it warmed my heart when the Times Style section sent a writer to Missouri to chronicle George Hodgman’s ongoing adventure with his mother. In my corner of Facebook, George is beloved. The bestseller list awaits. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here.For the Kindle edition, click here.]

For all that, there were lines in “Bettyville” that made this memoir impossible for me to read it, as others have, in one gulp. “My father could never have anything he wanted. He lived for us” — I know that story, and it’s not a happy one. “The world of the Dollar Store, the Big Cup, the carbohydrate, and the cinnamon roll” — I periodically make what I call Field Trips to America, and the wreckage of the land and the sadness of suburbia never fail to make me want to cry. Betty’s childhood poverty is touching: her mother sold milk to put her through college, her family was the last in town to get indoor plumbing. Most of all, there’s the presence of death on every page. As Le Rochefoucauld reminds us: “No man can look long at the sun or death.”

So, sometimes, I skimmed. And, though rarely, I skipped. And, once, for a day, I put the book down. Why return? Why volunteer for pain? “Sometime, at least once, everyone should see someone through. All the way home.” That is beyond admirable. To read to the end is to cheer for the proposition. And, of course, to cheer for George Hodgman.

“I wanted a place in the tribe,” he says. “I still do.”

And now the tribe mourns him.