Books |

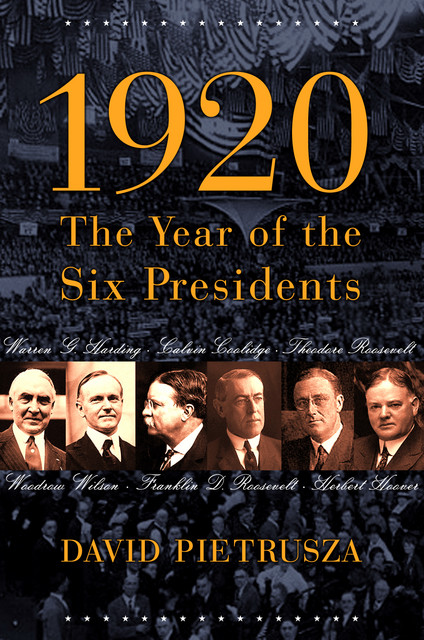

1920: The Year of Six Presidents

David Pietrusza

By

Published: Aug 27, 2013

Category:

Non Fiction

Guest Butler Billl Bodkin, a New York attorney and writer, is a student of American History. I’m not, so I’m delighted when he offers to school me. He last reviewed Revolutionary Summer: The Birth of American Independence.

My thoughts at the end of August inevitably turn to baseball’s pennant races (as a Mets fan, this takes only a few minutes), the impending cool days of Fall, and the American woman’s struggle for equal rights. Incongruous? Not really, as August 26th marks one of the milestone moments of the equal rights movement: the day in 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the United States Constitution.

The entire year of 1920 was, in many ways, a pivotal year in Twentieth Century American politics. For the reasons why, the curious need to look no further then David Pietrusza’s terrific “1920: The Year of Six Presidents,” a wild gallop of a read through that year’s campaign. Pietrusza organizes his book around the influence of six men who had been, or were soon to be, President.

Woodrow Wilson was, by 1920, felled by a massive stroke and was barely in control of the government.

Theodore Roosevelt’s life of perpetual motion was propelling him to seek the Presidency again until death intervened.

Warren Harding was, despite his Presidency, perhaps best remembered as a serial philanderer.

Calvin Coolidge, the taciturn Governor of Massachusetts, was Harding’s polar opposite and running mate.

Herbert Hoover was, writes Pietrusza, “a man whose cold efficiency saved more lives than all the eloquence and passion of a thousand politicians and statesman.”

The young Franklin Delano Roosevelt, then Assistant Secretary of the Navy and not yet crippled by polio, was the Vice-Presidential nominee on the 1920 Democratic ticket.

Pietrusza colorfully chronicles the battles for both parties nomination. The Republican efforts were hampered by the fact that “their logical candidate,” Theodore Roosevelt, was dead, while the Democrats were hampered by a living President in Wilson who would not and could not get out of the way. Pietrusza reminds us that Wilson’s incapacitation led to charges of “petticoat Government,” as his then wife, the former Edith Galt, whom he had married shortly after being widowed, controlled all access to him. [To buy the paperback from Amazon, click here. For the Kindle edition, click here.]

But perhaps the most significant role in 1920 was played by a woman. Not by any of Harding’s paramours. And not by the Mrs. President that Edith Wilson had allegedly become. The woman was Mrs. Febb Ensminger Burn, a widowed farmer in Tennessee. In his finest chapter, Pietrusza takes us through the final steps toward ratification of women’s suffrage. Congress had passed the amendment in 1919, sending it to the several states for ratification.

Twenty-two states ratified the Amendment in 1919, and then eleven more in the early months of 1920, leaving, by June 15, 1920, only one more state needed to ratify the amendment. By that time, only five states had yet to act on the amendment: Connecticut, Vermont, North Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee.

All of those state’s Legislatures were adjourned for the summer months, but on August 9, Tennessee governor Albert H. Roberts — who had been comfortably renominated in that year’s Democratic primary — called a special session of the Legislature. The Tennessee State Senate then ratified the Nineteenth Amendment by a resounding 25-4 vote. All eyes turned to the Tennessee State House of Representatives, which was led by Democratic Speaker Seth M. Walker.

Pietrusza tells us that Walker opposed suffrage, warning that it was “political suicide.” On August 18, Walker brought the bill to the floor, convinced he had the votes to kill it. The first two votes, on procedural matters, deadlocked 48-48. Ratification looked bleak. But at the last moment the youngest member of the Tennessee House changed his vote.

Twenty-four year old Harry T. Burn, who had, until that moment, been seen as a solid opponent of women’s suffrage, voted “Aye.” While it dawned on the chamber and the spectators that suffrage would pass, Burn tried to explain his change of heart. In his pocket he carried a letter from his mother, Mrs. Febb Ensminger Burn. She wrote:

“Dear Son: Hurrah and vote for suffrage! I noticed some of the speeches against. I have been watching to see how you stood, but have not noticed anything. Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt (women’s suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt) put the ‘rat’ in ratification. Your mother."

Pietrusza writes that "Burn knew that if it came down to him, he would have to cast his vote as his mother wished." As yellow roses, the symbol of the suffrage movement, rained down from the gallery in celebration, Burn fled the wrath of suffrage’s opponents, escaping “via a third floor ledge and hiding in the attic.”

When he emerged, he stated that he believed "in suffrage as a full right" and that he knew “a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow.” Mrs. Burn commented that she was “proud to say” that she and her sons were “pals,” and that she felt when the vote came “that Harry would see me smiling at him when he read that, and know his mother was with him in what we both knew was right.”

Burn, a Republican, did his best to claim suffrage as a victory for his party.

Women, casting many of their first-time Presidential votes for Harding and joining men in handing the Republican party a landslide, seemed to agree.

Thanks in no small part to the Burn family, August 26 is recognized in the U.S. as Women’s Equality Day. And while we set aside the second Sunday in May to honor our mothers, late August is as good a time as any to remember that maybe, just maybe, following their advice will make history.