Products |

Aaron Swartz: An open letter to his prosecutor

By

Published: Jan 14, 2013

Category:

Beyond Classification

I had a piece ready to publish about Highclere Castle, the English country house — okay: castle — featured in "Downton Abbey." This seemed more important. That is, "important" in the way that if you don’t do something, it’s a mark on your character. So. Apologies to those who don’t care, don’t agree or believe this is about nothing. But if you do see an issue here that might matter politically and culturally and personally, I ask of you a favor. On the upper right corner of the text on this page, there is a FORWARD TO A FRIEND button. (You have to type a few words into the message box — like: "This site never does this, but ‘never’ seems to have ended today" — or it won’t send. Sorry about that.) If you can think of people who might also care, would you send it to them? Thanks.

————

Carmen M. Ortiz

United States Attorney

District of Massachusetts

United States Federal Courthouse

1 Courthouse Way, Suite 9200

Boston, Ma. 02210

Dear Ms. Ortiz,

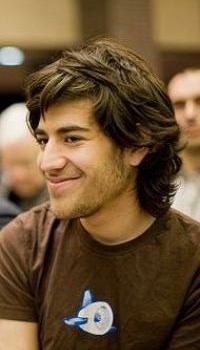

The suicide of 26-year-old Aaron Swartz has inspired an outpouring of commentary on the Internet, much of it about the role of your office in his death.

The general idea is that Swartz, though battling depression, didn’t so much kill himself as that you and your deputies, Assistant United States Attorneys, Scott L. Garland and Stephen P. Heymann, hounded him to his death.

No piece I’ve read has compared you directly to Javert, the police inspector in "Les Misérables," but it’s a fair analogy. As you’ll surely recall, Jean Valjean served almost two decades in jail, and, after being paroled, reformed so completely that he became a factory owner and mayor. But because Valjean had failed to report to his parole officer, Javert relentlessly pursued him. Valjean’s model citizenship, his honest business, his civic leadership — none of that mattered. Javert’s total focus was on Valjean’s “crime.”

I was reminded of Javert when I read your published comment on Swartz’s indictment. "Stealing is stealing whether you use a computer command or a crowbar, and whether you take documents, data or dollars," you said when your office indicted Swartz. "It is equally harmful to the victim whether you sell what you have stolen or give it away."

“Stealing is stealing.”

I’ve heard that before: “Crime is crime.”

I first encountered this unambiguous concept of crime and punishment two decades ago, when I was researching Highly Confident, my book about the criminal prosecution of financier Michael Milken. As part of my reporting. I went to Notre Dame Law School to interview Robert Blakey, the primary author of RICO (the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act). In discussing the 1931 movie, “Little Caesar,” Blakey explained that Caesar Enrico "Rico" Bandello (Edward G. Robinson) was not the real crime boss. That was “Big Boy,” who lived in a mansion of a hill, wore tuxedos and, in addition to running the city’s crime syndicate, was its mayor.

The police hunt Rico and kill him. “Big Boy” continues to rule. The law named after Rico, Blakely thought, might change that.

Rudolph Giuliani attended Blakey’s seminars, and when he became U. S. Attorney in New York, he used RICO to indict and convict the city’s Mafia leaders. Then, in the spirit of “Crime is crime,” he turned his attention to Wall Street. You have prosecuted white-collar crime, so you know how deadly a RICO indictment is to a legitimate business. Essentially, it’s punishment before trial — it cuts off access to credit and makes it impossible for the business to operate.

After Giuliani, prosecutors had a better understanding of RICO’s power, and we came to hear more about a concept I have not seen in any quotations attributed to you: “prosecutorial discretion.”

The Boston press has praised you for escalating prosecutions of white-collar crime. I see no prosecutions, however, of large institutions. Like your colleagues in other states, you seem to be plucking low-hanging fruit. Your idea of a big white-collar criminal seems to have been… Aaron Swartz. Why else would you approve a superseding indictment against him that could have put him in jail for 35 years, with a possible fine of $4 million?

"Crime is crime.” Ah, but what is the crime here?

The indictment against Swartz alleges the theft of “a major portion of JSTOR’s archive of digitized academic journal articles” from a closet at M.I.T. But JSTOR did not believe that Swartz committed a felony. (Over the weekend, it called Swartz “a truly gifted person who made important contributions to the development of the Internet and the Web from which we all benefit.”) Nor did M.I.T. (Over the weekend, its president said “It pains me to think that M.I.T. played any role in a series of events that have ended in tragedy.”) And now the expert witness for the defense in the trial that will never be has come forward to say he would have testified that no crime was committed:

If I had taken the stand as planned and had been asked by the prosecutor whether Aaron’s actions were “wrong”, I would probably have replied that what Aaron did would better be described as “inconsiderate.” In the same way it is inconsiderate to write a check at the supermarket while a dozen people queue up behind you or to check out every book at the library needed for a History 101 paper. It is inconsiderate to download lots of files on shared WiFi or to spider Wikipedia too quickly, but none of these actions should lead to a young person being hounded for years and haunted by the possibility of a 35 year sentence.

It is not unusual for the government to put pressure on defendants in an effort to force a plea. In the Milken case, prosecutors sent FBI agents to the home of Milken’s 92-year-old grandfather — who had no involvement with his grandson’s business — to ask him about his investments. Soon after that, Milken caved.

In Aaron Swartz’s case, his weakness was his depression. It was severe and persistent. He spoke often, and movingly, of it — it was anything but a secret. It’s no drug hallucination to suspect that you followed the Giuliani playbook, and, in amping up the charges against Swartz, you knowingly contributed to his depression. His suicide saves you the trouble of explaining yourself had a jury found him not guilty. Along with whatever remorse you may feel about Swartz’s death, it would only be natural if you feel a bit of relief.

Aaron Swartz was not just any defendant. He was a genius, an idealist, a political figure. In his campaigns, he had an agitator’s ability to recognize the third rail — and to reach out and touch it. Sparks flew. Others, fascinated and inspired, ran to his side. I don’t see that ending with his death.

Now the tables are turned. Aaron Swartz’s allies see you as the bad actors in this drama. Without benefit of a formal hearing, they have presented evidence and have found you guilty. And, for them, it’s time for you to take your punishment.

I see that there have been suggestions that you run for office, specifically Governor. You have said you are happy in your current job. I would suggest that you do not change that view, or, if you do, that you stay far away from electoral politics. Just from what I’ve read this weekend, I believe you would be the target of a relentless assault by progressive activists and digital programmers.

Finally, I would suggest that you beef up electronic security for your email and your documents. If Anonymous or individual activists aren’t now working to crash your firewall and download your mail and memos, I’d be surprised.

Does this seem like a disproportionate reaction? Only if, like Javert, you really believe you were prosecuting a single man. But from what I’ve read about the paucity of evidence in this case, it seems those who are writing about Swartz have presented a credible argument that you were trying to make an example of him — and that the real purpose of this prosecution was one more example of a corporate and government desire to tame and regulate the Internet.

If so….well, good luck with that.

Sincerely,

Jesse Kornbluth